Abortion, Persons, and the Fetus

From N. F. Gier, God, Reason, and the

Evangelicals

(University Press of America, 1987),

chapter 11.

Copyright held by author

In the rabbinic tradition...abortion remains a noncapital crime at worst.

--David Feldman

The law does not provide that the act abortion pertains to

homicide,

for there cannot yet be said to be a live soul in a body that lacks

sensation....

--Augustine

The intellective soul i.e., true person is created by God

at the completion of man's coming into being.

--Thomas Aquinas

Many modern philosophers and theologians return to St. Thomas' view.

--Joseph F.Donceel, S. J.

To admit that the human fetus receives the intellectual soul from the moment of its conception,when matter is in no way ready for it, sounds to me like a philosophical absurdity. It is as absurd as to call a fertilized ovum a baby.

--Jacques Maritain

Many people believe that the Roman Catholic Church's opposition to abortion stems from its conviction that a new human person exists from the first moment of conception...It is clear that this is not now, or has ever been, official church teaching on the matter.

--James T. McCartney

The Scriptures are silent in defining when one becomes a person.

--John Pelt

[The fetus] should not be called an unborn baby or unborn child ....It is certainly biological life, but life of a different order. We are not talking about intentional and unjustified slaying of a human being. [The word "murder"] should be dropped from the abortion issue....

--Bernard Nathanson

(of "The Silent Scream")

Many people have the impression that the Judeo-Christian position on abortion has always been as conservative as the current prolife movement. In his book Whatever Happened to the Human Race? Francis Schaeffer implies that abortion was an unthinkable practice in Christian countries before the 20th Century. The facts, however, are quite otherwise. In Christian England before the Norman conquest, the legal powers of a father followed the Roman tradition. A father could sell his own children as slaves if they were under seven years of age and he could lawfully kill any of his children "who had not yet tasted food."(1) Infanticide was widely practiced in all Christian countries until the 19th Century. The historian Lloyd de Mause quotes a priest in 1527 who said that "the latrines resound with the cries of children who have been plunged into them." (2) Criminal law of 17th Century France listed conditions under which a father had the right to kill his own children; and English midwives of the same period had to take an oath "not to destroy the child born of any woman."(3)

Historian Joseph Kett sums up this premodern view of the child: "Parents left their infants alone for long periods, seem to have been indifferent to their welfare, could not remember their names, refused to attend funerals of children under five, routinely farmed infants out for wet nursing, and argued in divorce proceedings, not over which parent should have the infant, but over which could send it packing." (4) We should remind ourselves that Kett is not talking about pagans here but church-going Christians.

We shall see that for Catholics the killing of an "unformed" fetus was not murder until a papal decree of 1869. Canon law on this point was not changed until 1917. But today leading Catholic philosophers and theologians disagree with this change. In Protestant countries the "forming" of the fetus was called "quickening," and abortions were permissible until that time. Even when stricter abortion laws went into effect in the 19th Century, very few cases of abortion of formed fetuses were ever prosecuted. Indeed, infanticide continued to be widely practiced, especially in the late 18th Century with the rise of the Industrial Revolution.

We shall also see that the Bible, especially if the image of God is the seat of personhood, cannot be used to support the current conservative position. Indeed, the traditional definition of the image forces Christians into a position much more permissive than current liberal views. We shall also demonstrate that arguments against abortion based on "unacceptable risk" or "potentiality" principles are untenable. It appears that, however poorly argued the 1973 Supreme Court decision may have been, the justices were most likely correct in implying that only the third trimester fetus can be said to have a serious moral right to life. Finally, one could argue that the fetus does at least have the right not to suffer unnecessary pain, and one could conclude that many abortion techniques must be banned if they are used on sentient fetuses. Allowing sentience in this sense, however, would then expand the moral community to include animals. Furthermore, 91 percent of abortions in the U.S. are performed in the first trimester before the fetus becomes sentient. Of the remaining abortions 9 percent are done in the second trimester and only 1 percent in the third.

ABORTION AND THE JUDEO-CHRISTIAN TRADITION

The ancient Jews were evidently liberal on the question of abortion: the fetus was not a person until birth. The Jews followed the Stoics and Romans who held that the fetus is a part of its mother; specifically, they believed that the fetus was the mother's "thigh" or "one of her limbs." Under rabbinic law the fetus has no power of acquisition; gifts or transactions made on its behalf are not binding; in short, the fetus has no judicial personality of its own. David Feldman sums up: "In the rabbinic tradition, then, abortion remains a noncapital crime at worst."(5) The Jewish tradition is unique in its stand about cases involving a threat to the life of the mother. In such cases the fetus is guilty as a "pursuer" under the negative commandment which demands that one may not "take pity on the life of a pursuer."(6) In such cases a therapeutic abortion to save the life of the mother is required rather than simply morally permitted as some modern thinkers believe.

In his book Death Before Birth Harold Brown gives the mistaken impression that Catholics and Protestants have always believed that we are persons from the moment of conception. This is simply not the case. Brown quotes from early Christians that were in the minority on this question. Christian orthodoxy was profoundly influenced by the first Greek translation of the Torah, done by Hellenistic Jews living in Alexandria in the Third Century B.C.E. This first Greek Bible, called the Septuagint and considered divinely inspired by some early church fathers, translates Exodus 21:22 in such a way as to make a clear distinction between an "unformed" fetus and one "formed." The moral implication of the verse is that the accidental destruction of an unformed fetus was punishable by a fine, but any killing of a formed fetus required "a life for a life."(7)

It is somewhat misleading to claim, as many Christian commentators do, that it was Christians who first began to protect the rights of the unborn. The pagan world did practice abortion and infanticide on a wide scale, but the Pythagoreans were an important exception. Because they believed in reincarnation, they thought that ensoulment occurred at conception. The theory of a truly eternal soul (person), embodied in all reincarnation doctrines, would be the best metaphysical defense of the conservative position on abortion. Some believe that the condemnation of abortion in the Hippocratic oath was not due to Hippocrates himself but to his Pythagorean disciples.(8) Some early Christians who condemned abortion from conception on, like Tertullian, St. Basil, and Gregory of Nyssa, could have been influenced by Pythagorean doctrine; since as we shall see, the biblical basis for such a view is vague and problematic.

The great majority of Christian theologians followed the Septuagint reading of Exodus 21:22 regarding the unformed and formed fetus. In his commentary on Exodus, St. Augustine writes that "the great question about the soul is not hastily decided by unargued and rash judgment; the law does not provide that the act abortion pertains to homicide, for there cannot yet be said to be a live soul in a body that lacks sensation when it is not formed in the flesh, and so not yet endowed with sense." (9) In the Enchiridion Augustine observes that "unformed fetuses are like seeds which have not fructified." (10) When Gratian brought together canon law for the first time in 1140, Augustine's view clearly prevailed: "Abortion was homicide only when the fetus was formed."(11) This remained the canon law position on abortion, with the exception of three years during the time of Sixtus V, until 1917.

In his comments on abortion Thomas Aquinas follows canon law, but his theory of fetal development appears to imply a more liberal position. Following Aristotle's tripartite theory of the soul, Aquinas claims that the zygote at conception has only a nutritive soul, which is later transformed into a sensitive (animal) soul after forty days, but ninety days in the case of females. (Aristotle's sexism was not only offensive but bizarre: he also believed that females had one less tooth than males!) For Aquinas the true person is not achieved until the sensitive soul is transformed into the rational soul: "The intellective soul is created by God at the completion of man's coming into being. This soul is at one and the same time both a sensitive and nutritive life-principle, the preceding forms having been dissolved."(12) By any reading of his theory of fetal development, Aquinas must be considered a liberal on the question of abortion.

Officially Western Christianity supported a doctrine of "mediate" animation, i.e., the fetus was not formed into a true person or soul until some time during pregnancy. The doctrine of "immediate animation" gradually gained support in connection with the doctrine of Mary's immaculate conception. This doctrine assumed that Mary's soul was perfect in every way from the very moment of conception. A clear implication of this was that ordinary souls, even though not immaculate, were also persons from conception.

In 1701 Clement XI made the immaculate conception a feast of universal obligation in the church. (13) The pope who made the final push for immediate animation was Pius IX, who finalized the doctrine of the immaculate conception in 1854 and then in 1869 declared that all abortions were homicide and required excommunication. In 1917 canon law was finally changed so as to dissolve the traditional distinction between a formed and unformed fetus. Other factors may have played a role in these significant decisions. Lawrence Lader observes that Pius IX was distressed at the tremendous increase in the use of contraceptives.(14) If ensoulment could be moved back to conception, then these practices would constitute much worse offenses. There was a long standing Catholic opinion that most abortions really stemmed from various "sins of sex."

Other scholars, primarily Catholic, emphasize the discovery of the laws of genetics and other knowledge about human reproduction. It is rather difficult to understand this alleged significance of the laws of genetics. Why should scientific genetics so radically change one's view of the soul? Actually, this would be a relevant point only for those who do not believe in the soul, like behaviorists and sociobiologists, who believe that all of our moral behavior can be explained in terms of genetic determinism. One would expect a Christian view of the person to be radically different from this.

Scientific materialists deliberately collapse the distinction between personhood and human species, but it is of the utmost importance for Christian theology to enforce this distinction. (Otherwise God or angels could not be called persons.) For Christianity, biology is about the "dust," but morality and religion deal with the spirit. Human beings are unique and valuable because they have spiritual natures separate from their physical natures. Therefore, Christians cannot draw on genetics as the primary basis for their doctrine of personal identity. Thomas Aquinas saw this clearly when he declared that the rational soul was not produced by human seed but by a direct act of God. The "genetic" argument is not only a poor reductionistic argument, but it is also a theological disaster for those Christians who use it.

Popular understanding would have us believe that modern Catholic philosophers and theologians have convinced their superiors that this genetic argument, or some other which supports personhood at conception, should be church doctrine. This is simply not the case. Jesuit John Connery states that "while it is true that the church today penalizes abortion at any stage, it would be wrong to conclude from this that it teaches immediate animation or infusion of a rational soul in the fetus. This it has never done."(15) James J. McCartney concurs: "Many people believe that the Roman Catholic Church's opposition to abortion stems from its conviction that a new human person exists from the first moment of conception...It is clear that this is not now, or ever has been, official Church teaching on the matter."(16) In a seminal article "Immediate Animation and Delayed Hominization," Jesuit Joseph F. Donceel argues that insofar as the church has affirmed Aquinas' hylomorphic theory of the development of the self, it must give up the concept of immediate animation in favor of "delayed hominization."(17) Donceel and many other Catholic philosophers and theologians now contend that the fetus is not a person until it has a rational soul.

Let us conclude this section on the history of abortion with some comments on English common law that began with Henry de Bracton (d. 1268). Up until Bracton the Anglo-Saxons considered abortion solely an ecclesiastical offense. Bracton was the first Englishman to place abortion under civil law, but again only if the fetus was formed and animated. The term "quickening" was introduced into the English language as a term for the animation or formation of the fetus.

During the 17th Century quickening as a cut-off point was abandoned in favor of birth. The following is Sir Edward Coke's description of English law in the mid-17th Century: "If a woman be quick with childe, and by a potion or otherwise killeth it in her wombe, or if a man beat her, whereby the childe dyeth in her body, and she is delivered of a dead childe, this is a great misprison, and no murder; but if the childe be borne alive and dyeth of the potion, battery, or other cause, this is murder; for in law it is accounted a reasonable creature, in rerum natura, when it is born alive." (18)

Under the influence of Sir William Blackstone (1732-80), the criterion of quickening returned as the accepted standard, was incorporated in early U.S. law, and remained in some state statutes until the Supreme Court decision of 1973. On the question of personhood, however, H. Tristam Engelhardt, maintains that "legal personhood in American law is achieved only at birth."(19)

Personhood and the Image of God

With their emphasis on biblical theology evangelical theologians feel no obligation to follow tradition or historical precedent on any issue. Evangelical Harold Brown indirectly criticizes the traditional Jewish position by claiming that basing a doctrine of soul on Genesis 2:7 is an "argument...seldom used by people who take Scripture seriously."(20) Surely Brown is pretentious to claim that rabbis for centuries have not taken their Torah seriously.

Evangelicals offer counter-arguments to liberal Christian views by appealing to various biblical passages. Two in particular appear to imply not only ensoulment in the womb, but even before conception. "Before I formed you in the womb, I knew you, and before you were born, I consecrated you" (Jer. 1:5). "Thou knowest me right well; my frame was not hidden from thee when I was being made in secret, intricately wrought in the depths of the earth. Thy eyes beheld my unformed substance (golem); in thy book were written, every one of them, the days that were formed for me" (Ps. 139: 15-16).

These are interesting passages but difficult to interpret. They also contain both logical problems and implications that a great majority of Christians would not want to accept. Orthodox Christianity has rejected the idea of the preexistence of the soul implied in both of these verses; and it is difficult to conceive of how even a divine mind could know something before it exists or know it as a possible existent. The passage from the Psalms maintains that the soul is formed in "the depths of the earth," which is a poetic phrase for Sheol, the Hebrew Hell from which all souls come and to which all souls return.(21) No orthodox Christian would want to accept this old Hebrew version of the creation of souls.

More significant is that the text of Psalm 139 may be corrupt, i.e., the words have been mixed up by scribes. Mitchell Dahood is convinced that the word golem was probably not in the original hymn. This is the only place in the Hebrew Bible where this word is used, so Dahood believes that the Hebrew syllables need to be "repointed" (for vowels) to read gilay-mi ("life stages").(22) If Dahood is correct, then the need to speculate about embryology is dramatically reduced. Dahood's Anchor Bible translation of these lines is the following: "My soul itself you have known of old, my bones were never hidden from you, since I was nipped off in the Secret Place [Sheol], kneaded in the depths of the nether world. Your eyes beheld my life stages, upon your scroll all of them were inscribed; my days were shaped when I was not yet seen by them."

In the Jewish tradition golem was not taken as a person at all; indeed, it was viewed as a being without a soul. In the Middle Ages a legend arose about an giant called a Golem that two Czech rabbis made out of river clay. They were presumably able to make the huge body live by reciting Kabbalistic chants over it. Jews in the Prague ghetto were able to protect themselves by having the Golem fight against Christians who attacked the ghetto on a regular basis. There was also the early silent film The Golem that stars a soulless monster bent on destruction. It is obvious that the Jewish meaning of golem is not compatible with the traditional definition of a person.

Harold Brown offers another reason why the creation account in Genesis 2:7 should not be used as a guide on this issue: it applies only to the creation of Adam. Adam's creation was unique because he was not conceived and borne in a womb. Therefore the criterion of God's infusion of the divine breath cannot be used as a criterion for personhood. Rather, the criterion is that God creates every human in the "image of God" (Gen. 1:26) and this special creation makes every human being a person.

One of the first problems with this argument for the abortion issue is that the Bible does not tell us when the imago dei is infused. As evangelical Paul Jewett states: "There is nothing in scripture bearing directly on the question of the participation of the fetus in the divine image."(23) The Jewish tradition maintains that birth is the time of infusion, and even C. F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, scholars highly respected by conservative Christians, reject Brown's distinction between the creations of Genesis 1:26 and 2:7 and implicitly support this Jewish view: "Man is the image of God by virtue of his spiritual nature, of the breath of God, by which his being, formed from the dust of the earth, became a living soul."(24)

Another difficulty with the imago dei argument is that in the New Testament the phrase (with only two exceptions) is used exclusively for Jesus Christ. Although Paul states that the man "is the image and glory of God" (1 Cor. 11:7), he must mean that this is man in Christ. Paul's sexism also complicates matters here: "[Man] is the image and glory of God; but woman is the glory of man" (1 Cor. 11:7). Does this mean that women are not full persons? (25) In 1 Cor. 15:42-50 Paul makes his theological anthropology clear: Only one human, Jesus Christ, was created in the image of God and all others were born in "the image of the man of dust." Only after we are Christians (or more properly, only in our resurrected bodies) will we "bear the image of the man of heaven."

The evangelical New Bible Dictionary supports this Christocentric interpretation of the image of God: "Man must be still regarded as in the image of God, not because of what he is in himself, but because of what Christ is for him, and because of what he is in Christ...In Christ, by faith, man finds himself being changed into the likeness of God...In "putting on" this image by faith, he must now "put off the old nature," which seems to imply a further renunciation of the idea that the image of God can be thought of as something inherent in the natural man...."(26)

Although agreeing with this basic point about the New Testament imago dei, the author of this article, R. S. Wallace, goes on to contradict himself in his attempt to harmonize Paul and the Hebrew Bible Testament. If we put on the image of God by faith, then Wallace cannot talk about us being created in the image of God. Nor can he speak of this created image being "marred" and then through Christ reaching "full conformity to His image." Either the image of God is innate and natural to man through creation, or it is not natural and is given by virtue of our humble faith as mortals, born as we are in "the image of the man of dust" rather than in "the image of the man of heaven." If the imago dei resides only in Christ, then no non-Christian can be a person in this sense. No theologian would want to build a theory of personhood on such a discriminatory basis.

Finally, new archeological evidence from an Assyrain inscription at Tell-Fekheriyeh indicates that all traditional interpretations of the image of God may be incorrect. The inscription includes a translation in Aramaic, a language very close to Hebrew and probably Jesus’ mother tongue. The Aramaic equivalents of the "image" and "likeness" of God are found in this text and the meaning is that Assyrian king rules with God’s authority on earth. This meaning fits very nicely with Adam having dominion over the animals and the New Adam having redemptive dominion over the universe. But this is an exclusively political meaning of "image of God," and cannot be used any discussion about human nature. (26a)

We have seen that Clark, Nash, and Henry contend that reason has priority in the image of God, but a broader notion of "significant mental life" may be preferred. James Sire, editor of Intervarsity Press and a professor at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, maintains that the image of God means "that, like God, man has personality, self-transcendence, intelligence...morality (capacity for recognizing and understanding good and evil), gregariousness or social capacity...and creativity." (27) Paul Jewett of conservative Fuller Theological Seminary states that the image of God "defines a man as a man, a person, an individual that is free and self-conscious, and a rational, moral, and religious agent and one that is aware of an 'I-Thou' relationship to his Creator." (28)

Sire and Jewett are to be commended for emphasizing the sociability criterion, one which will also be important for the definition of a person in the section after next. But the implication for the abortion debate is clear: the evangelicals' own definition of the imago dei excludes the fetus as a person. Indeed, without Roland Puccetti's distinction between a "beginning" and "actual" person, their criteria would definitely disallow infants as persons. Furthermore, Sire's strict moral standards would eliminate personhood for minors and the mentally retarded; and his creativity criterion, depending on what he means by it, could exclude a great many deserving people from the realm of persons.

CUT-OFF POINTS IN FETAL DEVELOPMENT

From the side discussion on biblical issues, we again we see the futility of appealing to the authority of religion and all the problems that this involves. As it is clear that outside philosophical speculation has played a profound role in interpreting the image of God, we might as well rely on our own analysis for defining a person. Various points during fetal development have been suggested as significant stages at which simple biology gives way to full personhood. The Supreme Court decision of 1973 chose viability; today's conservative Christians and Jews insist on conception; and as we have seen above, historical Christianity chose animation in the womb, while historical Judaism opted for birth. Let us analyze each of these points in turn for their philosophical merit.

All higher animal life begins at conception, so no moral significance can be given an event common to all mammals. Nevertheless, John T. Noonan argues the following: considering the fact that there are 200 million spermatozoa in a single ejaculate and that there are between 100,000 to a million oocytes in a female infant, Noonan argues that nature (God) is trying to tell us something morally significant about the relative worth of a zygote, which develops successfully into a new being 80 percent of the time, as opposed to the thousands of eggs and billions of sperms that are simply wasted in a normal lifetime.(29)

Noonan does not give a reference for his claim for the 80 percent success rate, but the rate appears to be drawn from studies done on spontaneous abortion after implantation. Reproductive physiologists suspect that there is a much larger failure rate before implantation (perhaps over 60 percent), but there is no way of testing this precisely. Whatever the rate is, Noonan has failed to establish any moral difference between humans and animals in this area. Facts are difficult to come by, but some biologists have reported that Rhesus monkeys also have an 80 percent success rate after implantation.

Noonan himself mentions the fact that there is the possibility of twinning for twenty days after conception. He states that the probability of this happening is very low, but he misses the significant philosophical implication that twinning holds. If personhood begins at conception, then what happens to a single person when there is twinning at twenty days? The absurd implications are clear. One Dutch Catholic theologian explains: "This fact the possibility of twinning shows that biologically speaking the fecundated ovum is not yet wholly individual. For, although its hereditary virtualities are set, a cellular division may change it into more than one individual....As long as such a possibility exists, the philosophical definition of individual, which explains it as 'undivided in itself,'...is not yet realized...." (30) We must conclude that there is no morally relevant difference before or after conception. Furthermore, the zygote definitely does not exhibit any of the characteristics of a person. At most the zygote is a potential person and we shall discuss the effectiveness of the so-called "potentiality" principle in the last section of this chapter.

In human persons the brain is the physical basis for the mental lives we pursue. At the end of four weeks the human embryo has a spinal cord and a primitive brain with two lobes. Brain waves can be detected at this early stage and some have proposed this as a morally significant cutoff point. This brain activity, however, is no different from that of other animal fetuses, so there can be no morally relevant difference at this stage.

After informing us that electrical activity, neural connection, and the presence of neurotransmitters are required for sentient life, biologist Clifford Grobstein describes the six-week-old embryo: "There is no demonstrable electrical activity characteristic of the nervous system....Although a rudiment...can be identified...none of the essential features for characteristic function are there. The cells that make up the rudiment are still in rapid division and have not yet become nerve cells. There are no characteristic connections among them. Correspondingly, neurotransmitters have not yet appeared. If sentience depends upon any aspect of neural function, it cannot possibly yet be present....If some aspect of self does exist at this stage, it is equally likely to be present in all living cells and organisms; it is not the kind of self that we experience so intimately and vividly."(31) All of the preceding criteria, plus the development of the neo-cortex are in place by the third trimester; and this does constitute a significant biological fact with regard to personhood.

Prolife debaters sometimes show pictures of aborted fetuses to prove that the eight-week-old fetus is a human being. Biologically, it is a human being, but having human form is only incidental to being a person. God would not have a human form, yet God would be a person if God existed. ETs would be persons but they would not necessarily look like us. Besides, we could conceive of human beings without arms, legs, ears, noses, and other bodily parts, but we would still have to consider them persons. Indeed, the disembodied brain of science fiction would still be a person. Furthermore, an early gorilla fetus looks very much like a human fetus, and modern dolls have an amazing human likeness, but of course these things are not persons.

As we have seen, English and American laws have used the criterion of quickening as a dividing line between legal and illegal abortions. But the fact that fetuses have the ability to move about spontaneously in the womb cannot possibly have any moral relevance. It would make most machines persons, but deny personhood to the paralyzed human being. Animal fetuses move too, but they do not acquire special rights because of this. The movements of a nine-week-old human embryo have been compared to the flapping motion of the tail fin of a fish. By fourteen weeks fetal mobility has become more graceful, but biologists like Grobstein are not sure if this is true sentient responsiveness or something "not basically different from that commonly observed in the young frog tadpoles that lie at the bottom of a dish and occasionally, for no apparent reason, erupt into vigorous swimming movements...."(32)

Although there are certainly problems with the viability criterion, this concept has been treated unfairly in the literature. Objections that fetal transfers from one womb to another, now done in some animals, could be done in humans or that artificial wombs and placentae will soon be available miss the point. These new procedures would not change the fact that the fetus is still in a womb and still completely dependent upon it. Furthermore, viability alone without significant brain development would not be a sufficient condition for being a person. The argument that fetuses are dependent in a significant way on other people until they are three or four years old also misunderstands the concept of viability: even though the infant still needs care, it is physically independent from its mother. Critics have misfocused on dependence when the crux of the matter is separate existence. Siamese twins using the same vital organs, people on kidney dialysis, and the disembodied brain of science fiction are all dependent beings; but they are persons because they are independent centers of conscious awareness with their own personal identity.

The main problem with the viability criterion is the fact that it is based on an empirical variable: some fetuses (particularly African ones) are viable before others. A second empirical test ought to be used to tighten up the concept of viability. The concept of person requires not only physical independence in the world but also a significant mental life. Neocortical brain waves commence at the beginning of the third trimester, the period of viability stated in the Supreme Court decision and verified by special medical commissions. By the sixteenth week the fetal brain has assumed the structure and shape of the adult brain, including the growth of the cortex, a mantle of nerve cells covering the cerebral hemispheres. Furthermore, the 100 billion neurons of the adult brain have been formed in the fetal brain by the twentieth week.

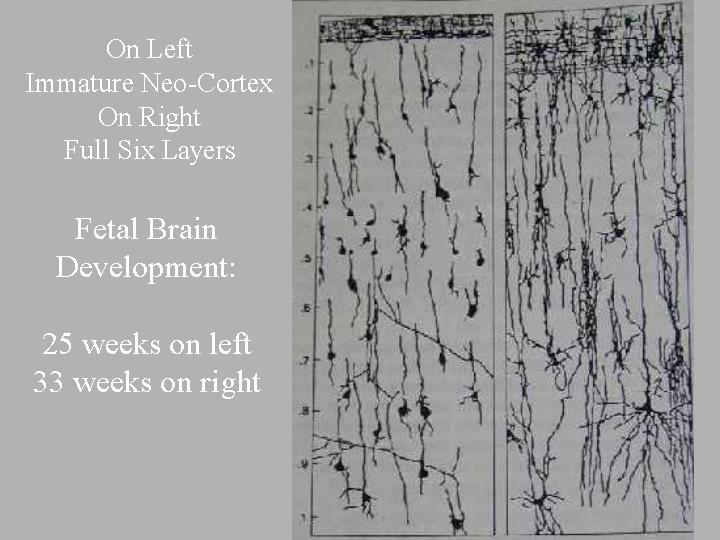

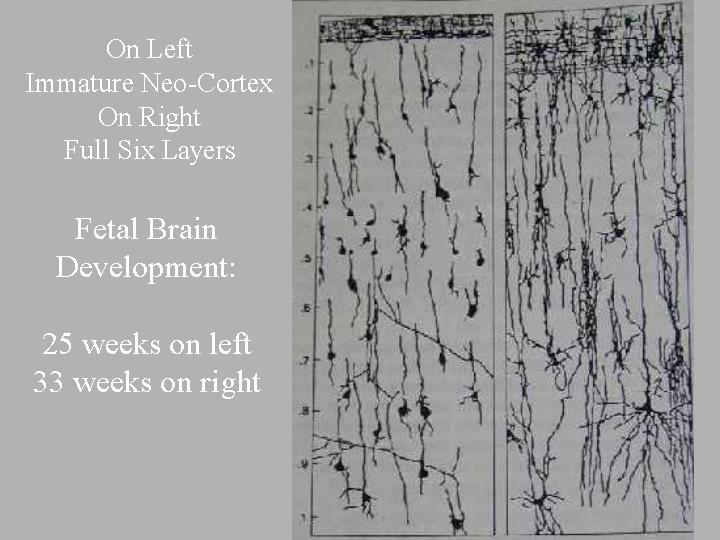

Advanced brain research has shown, however, that intelligence depends not so much on brain size or even the number of brain cells; rather, the most important elements are the interconnection and complexity of these cells. The catalysts for this development are the glial cells, which nourish the neurons and cause the growth of a sheath of myelin around each neuron. Myelin works like an electrical insulator and protects specialized neural activity from random interference. Myelination increases rapidly between twenty-eight and thirty-two weeks. This explosive brain development in the third trimester is a significant empirical factor. It represents the time at which the mental life of the fetus would be qualitatively different from other animals. Study the diagram below and notice that the brain cells on the left are not yet connected and the neocortex has not developed its six layers.

By observing rapid-eye movement in premature babies, it has been discovered that fetuses spend a great part of their time (70-80 percent at 32 weeks) dreaming during this period. Brain scientists speculate that this increased brain activity must reflect the rapid development of neural connections, although the number is far short of the 10,000 which each adult brain cell has. In addition, the cortical layer starts folding under itself to form the neocortex, which has six different layers in the adult brain, and which plays an essential role in the distinct mental experiences of human persons.

BEGINNING AND ACTUAL PERSONS

Throughout history most human beings have slowly but surely learned to respect all living things, but it is only to persons that we grant a serious moral right to life. For example, I respect the lives of wasps as long as they and their nests are at a safe distance; but I have no compunction about killing them if they make a home in my chimney and begin to attack me. Wasps obviously have no serious moral right to life. Even though persons can sometimes be as annoying as wasps, we must treat them very differently. Persons are the most valuable things in the cosmos. Without them morality and ethics would be impossible. Philosopher H. T. Engelhardt says that what Rolland Puccetti calls "actual" persons are "the moral agents of the universe. They are the entities who are responsible for their actions and who are bearers of both rights and duties."(33)

We can develop a definition of a person by analyzing the way that we use the word. Believers call God a person and many of these same people would also say that angels are persons. Those who are nonbelievers would certainly grant the possibility of the existence of extraterrestrial persons. The basic premise of the movie "ET" was that ET was a person and that all ETs, like the movie's hero, would have a serious moral right to life. What are the common features of these persons? First, it is clear that a person must be an independent being. The ancient Hebrews, Romans, and Hindus recognized this in their belief that the fetus was part of its mother. The Hindus said that the "woman's fetus is a limb of her own"; and the Hebrews and Romans agreed that the fetus "be accounted as part of the mother's belly."(34) Perhaps the Supreme Court in 1973 was correct in emphasizing the viability of the fetus.

Second, persons have mental lives qualitatively different from animals. Following Rolland Puccetti, one can distinguish between a "beginning" person and an "actual" person. (35) As we have already discussed, this mental life not only includes cognition, but also emotions, imagination, and creativity. Beginning persons must have the basis for this mental life, but they do not have to be responsible, self-determining beings. This means that beginning persons are moral objects with rights, but they are not yet moral agents with duties. Actual persons are moral subjects with rights, duties, and full responsibility for their acts. Human beings become full persons at the age of majority, while God and angels would always be actual persons.

Third, persons are social creatures. As we have seen, growing consensus in philosophy, theology, and the social sciences maintains that interaction with others is crucial for the development of personal identity. The persons mentioned above could engage in social intercourse, not only with their own kind, but with each other. (For example, in the Bible humans talk with God and angels and in science fiction kids socialize with ET, and mixed musical groups and armies appear in Star Wars.) Most of contemporary philosophy and psychology has turned away from the Cartesian-Kantian isolated ego and has supported a dialogical view of personhood. The most eloquent spokesman for this idea is Martin Buber, who in his famous book I and Thou said: "I require a You to become; becoming I, I say You"; or "there is no I taken in itself, but only the I of the primary word I-Thou...." (36) Only when a human being learns to say "Thou" does he or she, according to Buber, become a person. Engelhardt agrees: the fetus is not a "who" who can be addressed, because there can be no true dialogue between it and the external world. Engelhardt believes that it would be nonsense to ask people who they were or what they were doing before birth.(37)

God is obviously a person in terms of the preceding discussion, but there is still an important qualification that must be made in terms of God and personal relations. These we have of course with other human persons and could have with extraterrestrial persons and angels if they exist. But God does not exist in the same way that these persons exist. God's omnipresence and essential hiddenness would make our relation to the divine being very different from ordinary social intercourse with finite persons. Contrary to biblical claims, it is impossible for any of us to see God face to face; and God is not able to speak to us in words or communicate with us by physical gestures. Some theologians say that the universe is God's "body" so one could say, by analogy only, that God communicates through the magnificent "gestures" of nature.

These three factors--independence, significant mental life, and sociability--now constitute the necessary conditions for being a person. (Note that none of them in itself is a sufficient condition.) It is obvious that a strict application of these criteria would mean that the fetus is not a person, and therefore does not have a serious moral right to life. Such a view would be the same as the ancient Hebrews who believed, as we have seen, that the fetus was not a person until birth. On the basis of fetal brain physiology discussed above, it would be reasonable to propose that the third trimester fetus be considered a "beginning person." Crucial brain development comes at the same time that the fetus becomes viable and can in normal circumstances live independently outside the mother's womb. A fetus born at this time would fulfill all the requirements of beginning personhood listed above. Birth as a cut-off point essentially collapses into viability, because a viable fetus could experience a successful birth at any time. Therefore, the third trimester fetus should be treated as a moral object with a serious right to life.

Various criticisms can be raised against this position, and in the space remaining, we will respond to them in turn. Applying the consciousness criterion too strictly, some critics charge that sleeping people must forfeit their personhood and that this is obviously absurd. But just as obvious is the fact that there is no known brain impairment due to sleep. Furthermore, those individuals will awake to continue a personal life which has already been established, naturally and legally, in the world. The same goes for the senile and most of the mentally handicapped, who do not lose consciousness or even most higher brain functions. Down's syndrome, for example, does not affect the structure of the brain, but seems only to lower the cerebral metabolic rate. One Mongoloid child's IQ was measured at 116, but most are below 50 with only 5 percent below 20. Experts are now convinced that many more of these individuals are educable than previously thought.

Even most severely retarded individuals have mental lives older than third trimester fetuses. It is only brain-dead comatose humans like Karen Ann Quinlan and severely defective infants like Baby Ashley (with 85 percent of her brain missing), who do not meet the requirements for beginning persons. In these cases active euthanasia should be morally permissible. As long as Quinlan's brain was functioning normally, she should have been kept alive; but when her brain atrophied to a third of normal size, it was an insult to the dignity of the person she once was to allow her to continue a life totally devoid of personal qualities. Using Puccetti's categories, we can say that Quinlan, once an "actual" person, became only a "former" person. Quinlan's case reveals a clear distinction between a person and a biological human being; and it demonstrates that we can have human beings who are not persons (e.g., Quinlan) and persons who are not human beings (e.g., ET).

Others might respond that, according to my criteria, we would have to recognize dolphins, whales, and chimpanzees as beginning persons. This indeed is a possibility, but one so controversial that it is too early to make a firm decision. Chimps and gorillas who have learned sign language and socialize with human beings might be persons; but there are a growing number of experts, led by Herbert Terrance of Columbia, who have disputed this. John Lilly claims that dolphins are far superior to human beings: compared to the several-million-year evolution of the human brain, the dolphin brain, with 40 percent more cortex than humans, has been around for 15 million years. Lilly even contends that dolphins are spiritual beings, but he is the only person who holds this view. Nevertheless, we must leave open the possibility of terrestrial persons, just as we must for extraterrestrials.

In this section we have argued that the straightforward logic of persons cannot grant that the fetus is a person before the third trimester of its development. What we have done is essentially support the Supreme Court decision of 1973, which ruled that the mother's right to privacy takes precedence over any other claims of or for the fetus until the third trimester. This position differs from the Supreme Court's in one significant respect: the justices argued that there was no consensus--philosophical, theological, or scientific--about when a fetus becomes a person. We have shown that the good justices should not have been so hesitant on this matter.

The implications of this position for the contemporary religious debate on abortion are also instructive. We have already seen that many Catholic philosophers and theologians are returning to Aquinas' view of delayed hominization, and it is significant that they choose some of the same criteria as we do in determining personhood. For example, Joseph Donceel states that "if form and matter are strictly complementary, as hylomorphism holds, there can be an actual human soul only in a body endowed with the organs required for the spiritual activities of man. We know that the brain, and especially the cortex, are the main organs of those highest sense activities without which no spiritual activity is possible."(38) One of the most distinguished Catholic philosophers of the 20th Century, Jacques Maritain, has declared that "an intellectual soul presupposes a brain, a nervous system, and a highly developed sensitivo-motor psychism....To admit that the human fetus receives the intellectual soul from the moment of its conception, when matter is in no way ready for it, sounds to me like a philosophical absurdity. It is as absurd as to call a fertilized ovum a baby." (39)

UNACCEPTABLE RISK AND THE POTENTIALITY PRINCIPLE (40)

John V. Wagner of Gonzaga University has presented a case for the "unacceptable risk argument," one which has been used by some prolife advocates. Wagner illustrates this principle with the proverbial story of the hunter shooting at what he thinks is a deer in the bushes. The unacceptable risk principle simply requires that a hunter with any moral sense will make absolutely sure that the creature in the bush is not a cow or another person. Wagner then argues that since there is so much controversy about when the fetus becomes a person, it is always an unacceptable moral gamble to take the life of the fetus at any stage in its development. Furthermore, Wagner argues that this formulation of the antiabortion argument shifts the burden of proof away from the conservatives, who no longer have to prove that the fetus is definitely a person from conception on, to the liberals, who now have to prove that the fetus is definitely not a person. (41)

The main problem with Wagner's argument is that he is unnecessarily agnostic about the development of the fetus. Physiological knowledge about the nature of the fetus is not analogous to the hunter guessing at what is moving in a bush l00 yards away. Our knowledge of fetal development is incredibly detailed and it is growing all the time. Wagner's claim that there is no significant "metamorphic change" in the development of the fetus can easily be challenged. We have argued that the appearance of neocortical brain activity could certainly be called significant; and this event coincides with the traditional definition of a person found in our European tradition, including the theological tradition about the image of God. No one should have any difficulty in assuming the burden of proof and that we now know enough about the fetus to be confident that abortion, until the third trimester, is not an unacceptable moral risk.

Although it is clear that conservatives fail in their attempts to ascribe personhood to the conceptus, we must concede that the fetus from conception on is a potential person. Aquinas was actually quite near the truth that human fetuses are mere "sensitive" souls until late in pregnancy. As we have seen, the neocortical brain development necessary for a beginning person commences in the third trimester. Even though the fetus is only an animal until this time, it is significant that the human fetus is the only animal which, as far as we know, develops into a person. They are the only fetuses that are potential persons. To argue that it is morally wrong to take the life of a potential person is to use what Michael Tooley calls the "potentiality" principle. The arguments which Tooley and Engelhardt muster against the potentiality principle may not be entirely convincing. (42) The principle does fail, however, for other reasons.

Engelhardt contends that the use of the potentiality principle involves a semantic confusion between future and present predicates, which would then imply that ontologically a thing now has the qualities that it will have in the future. As a result, Engelhardt says that "one loses the ability to distinguish between the value of the future and the value of the present." (43) Some examples show the absurdity of this interpretation of the potentiality principle. An associate professor is a potential full professor and will be promoted only after completing significant professional work. Using the potentiality principle, all associate professors could argue that they are already entitled to the privileges and prestige of a full professor. Similarly, resident aliens could argue that they need not go through with the naturalization process because potential U.S. citizens have the same rights as actual citizens.

Those who use the potentiality principle need not accept this obviously absurd version of the principle. They could simply argue that the fetus as a potential person, although it cannot claim the rights of a person (either "beginning" or "actual"), it still has the right to develop its potential as a person. After all, using the examples above, it would be wrong to deny the junior professor or the alien the right to pursue their respective advancement in society. Even with this more favorable interpretation of the potentiality principle, there is something basically wrong with these examples used as analogues with the developing fetus. Professional promotion and naturalization are not natural developments which happen as a matter of course; rather, they are societal achievements which require initiative and conscious choice. The fetus does not choose to be conceived and does not choose to become a person.

The foregoing observation does not invalidate the potentiality principle. One might hold that a potential which is not developed by conscious choice has no moral significance. But this is clearly mistaken. A ten-year-old child, who has the natural potential to become twenty years old, certainly has a legitimate moral claim to the right to become twenty. It would surely be absurd to maintain that one has to choose to be twenty in order to have the moral right to. Therefore the fetus' potential personhood is what William Hamrick calls a "real" potential as opposed to the "theoretical" potential of becoming a full professor or U.S. citizen.

There was, for example, nothing inevitable about my becoming a philosophy professor, but it was inevitable under normal circumstances that my natural potential to become a person was fulfilled. At my conception the genetic material which guided my brain to eventually produce neocortical impulses was already there. William Hamrick phrases it aptly: "The zygote is already potentially what it will actually be as a mature infant. Its potentiality is real, not merely theoretical because, although its morphology and capacity for experience are sketched only in outline, it is nonetheless a real outline. This is not, as it may appear, a mere play on words. Rather, it is to enforce the conclusion that, although there is in the zygote only a blueprint of the finished structure, the blueprint has the singular peculiarity of being built into the structure." (44)

The genetic procedures of cloning offer a better argument against the potentiality principle. With the technology of cloning, every cell in a person's body is a potential person. The complete genetic material in each cell simply has to be transplanted in a viable ovum and then placed in a womb. The cloning hypothesis is a good example to show the confusion of genetic and personal identity which is found in many conservative arguments against abortion. If we took the genetic material of 1000 cells from one person's body and transplanted it in 1000 ova in 1000 wombs, how many potential persons would we have? Only one person according to the genetic-based arguments of many conservatives. But this potential "person" would become 1000 different persons according to current law and the definition of personhood outlined above.

A critic might reply that ordinary body cells do not naturally clone themselves. Only when human germ cells come together as a fertilized egg is there a natural development towards personhood. Body cells are therefore not potential persons unless cloning is artificially introduced. The zygote is the only natural potential person. There is, however, a flaw in this reasoning. The conservative, after winning recognition for the moral significance of the conceptus' potential personhood, has now forgotten that some theoretical potentials also have moral relevance. Short of extenuating circumstances, it would not have been right for the administration of the University of Idaho to have denied my promotion to full professor, especially after five productive years in rank. But as we have argued above, there was no natural potential at my conception which would have resulted in this particular achievement in my life.

The theoretical potential of sperms and eggs to come together to become zygotes or the theoretical potential of cloning body cells definitely establishes these entities as potential persons. Experimentally induced parthenogenesis has been successful with animals, and unlike cloning, it is more technically feasible in human females. As this process requires a fairly simple biochemical stimulus, there is a possibility that even some human females have given birth without need of the male gamete. (45) If the potentiality principle is to be applied consistently, the life of ova and sperm should be protected as carefully as the conceptus. This of course constitutes a reductio ad absurdum argument against the potentiality principle.

At the beginning of this chapter we documented the lack of concern that premodern peoples, including Christians, had for their children. It is a sad irony that the first successful moves to protect children's rights were made by English reformers using laws for the humane treatment of animals as their legal precedent. Even though conservatives have been unsuccessful in proving that the fetus, at least up until the third trimester, is a person, it is still an animal with the rights that we grant to higher mammals. For example, although we can kill a dog humanely, it is wrong to torture it. It might be the case that some abortion techniques are indeed a form of torture and they should be outlawed on that basis. This would be an issue only after the fetus has become sentient, and this is not the case until at least the second trimester. As 91 percent of all abortions in the U.S. are done within the first three months, this suggestion is not as radical as it might appear at first.

Chapter 11 of N. F. Gier’s God, Reason, and the Evangelicals (Lanham, MD: University of America Press, 1987). Copyright held by author.

ENDNOTES

1. Quoted in Lee E. Teitelbaum and Leslie J. Harris, "Some Historical Perspectives on Governmental Regulation of Children and Parents" In Beyond Control: Status Offenders in the Juvenile Court, eds. Teitelbaum and Aidan Gough (Cambridge, MA: Ballinger, 1977), p. 2

2. Quoted in Lamar Empey, American Delinquency: Its Meaning and Construction (Homewood, IL: The Dorsey Press, 1978), p. 27.

3. Quoted in ibid.

4. Quoted in Charles Krauthammer, "What to do about Baby Doe?" The New Republic (September 2, 1985), p. 20.

5. David Feldman, Birth Control in Jewish Law (New York: New York University Press, 1968), p. 255.

6. Feldman, pp. 275 ff. See also R. H. Feen's article in William B. Bondeson, et al., Abortion and the Status of the Fetus (Dordrecht: Reidel, 1983), p. 166.

7. Some of my critics object to the use of the Septuagint, because they claim that it is a faulty translation. I am not an expert on these textual matters, but I can at least see an unfounded presumption on their part. We do not have the original Hebrew text from which the Septuagint was translated, so we cannot say whether the translation is correct or incorrect. The crucial point is that for five centuries this translation was considered inspired and authoritative by many in the early church.

8. Lawrence Lader, Abortion (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merill, 1966), p. 76.

9. Augustine, On Exodus, 21.80.

10. The Enchiridion, Chapter 85 in Basic Writings of St. Augustine, vol. 1, p. 708.

11. Quoted in Jane Hurst, The History of Abortion in the Catholic Church: The Untold Story, p. 11.

12. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I, q. 118, art. 2.

13. See Hurst, p. 16.

14. See Lader, p. 80.

15. John Connery, Abortion: The Roman Catholic Perspective (Chicago: Loyola Univeresity Press, 1977), p. 212.

16. James J. McCartney, "Some Roman Catholic Concepts of Person...," Abortion and the Status of the Fetus, p. 313.

17. Joseph F. Donceel, "Immediate Animation and Delayed Hominization," Theological Studies 31 (1970), pp. 76-105.

18. Quoted in Cyril C. Means, "The Law of New York Concerning Abortion and the Status of the Fetus, 1664-1968," New York Law Forum 14 (1968), p. 420.

19. H. T. Engelhardt, "Introduction" to Abortion and the Status of the Fetus, p. xxii.

20. Harold O. J. Brown, Death Before Birth (New York: Thomas Nelson, 1977), p. 124.

21. Mitchell Dahood, The Anchor Psalms, vol. 3, pp. 284, 294.

22. Ibid., p. 295. Even if one stays with the word golem, the Jewish tradition has maintained that it means unformed and unsouled (see Carol Ochs, Behind the Sex of God, [Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1977] p. 8). The Golem of Medieval Judaism was a monster without a soul.

23. Paul K. Jewett, "The Relationship of the Soul to the Fetus," quoted in L. P. Bird, "Dilemmas in Biomedical Ethics" in The Horizons of Science (New York: Harper & Row, 1978), p. 140.

24. C.F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, Commentary on the Old Testament, vol. 1, p. 64. The evangelical Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament also concurs: "God's image obviously does not consist in man's body which was formed from earthly matter, but in his spiritual, intellectual or moral likeness to God from whom his animating breath came" (vol. 2, p. 768).

25. The church fathers unfortunately took this verse very seriously. Tertullian states: "You [woman] are the devil's gateway...How easily you destroyed man, the image of God" (quoted in Mary Daly, Beyond God the Father [Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1973], p. 44). Augustine believed that the image of God resided only in the male; females would have it only in their sexless resurrected bodies (De Trinitate, XII, 7).

26. New Bible Dictionary, p. 777/732 (2nd ed.). Evangelical Michael Green also claim that Paul believes that the image of God is found in "his beloved Son" alone (The Truth of God Incarnate, p. 20).

26a. See Barry Bandstra, Reading the Old Testament (Belmont,CA: Wadsworth, 1995), p. 60-61

27. James W. Sire, The Universe Next Door (Donwer’s Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 1976), p. 31.

28. Paul K. Jewett, quoted from class notes by John Pelt, The Soul, The Pill, and the Fetus (New York: Dorrance, 1973), p. 31.

29. John T. Noonan, "An Almost Absolute Value in History" in The Problem of Abortion, pp. 14-15.

30. P. Schoonenberg, God's World in the Making, p. 50; quoted favorably in Donceel, op. cit., pp. 98-99.

31. Clifford Grobstein, From Chance to Purpose (Reading, MA: Addison-Weslely, 1983), p. 88.

32. Ibid, pp. 91-92.

33. Engelhardt, "Viability and the Use of the Fetus" in Bondeson, p. 185.

34. David Feldman, op. cit., p. 253; Aitareya Upanishad 2. 4. 2; Plutarch, De Placitis, 15.

35. Roland Puccetti, "The Life of a Person" in Bondeson, pp. 169-181.

36. Martin Buber, I and Thou, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1970), pp. 54, 62.

37. Engelhardt, "The Ontology of Abortion," pp. 219-20.

38. Donceel, p. 83.

39. Jacques Maritain, "Vers une thrie thomiste de l'evolution" p. 96; translated and quoted by Father Donceel in a letter to me, January 17, 1984.

40. This section was originally part of a paper presented at the Northwest Conference on Philosophy at Seattle University, November 1981. I am grateful to former students in Philosophy 103 for their inventiveness in coming up with most of the arguments against Tooley's and Englehardt's criticisms of the potentiality principle.

41. John V. Wagner, "The Effectiveness of Various Arguments for the Humanity of the Unborn," unpublished conference paper.

42. See Engelhardt, "The Ontology of Abortion" and Michael Tooley, "Abortion and Infanticide." I have deleted my arguments against Tooley because of space limitations.

43. Engelhardt, "The Ontology of Abortion," p. 223.

44. William S. Hamrick, "Abortion: A Whiteheadian Perspective," an unpublished 1980 paper available at the Center for Process Studies, Claremont, California, p. 25.

45. Again Jesuits Donceel and Schoonenberg are my source for this information. Donceel states that "even an unfecundated human ovum would be potentially, virtually, a human person. Does each such ovum possess a human soul?" (p. 99).