First published in

Women in Forestry 5:2, Summer 1983

The date was May 12,

1913. The place was Sawyer’s Bar in the rugged Siskiyou Mountains of

northern California. The letter was addressed to Mr. W.B. Rider,

Supervisor, Klamath Forest. The writer was Mr. M.H. McCarthy, Assistant

Fire Ranger. His purpose in writing was twofold: first, to inform Mr.

Rider that W.R. McDowell, who had served “so well” as Fire Lookout at

Eddy’s Gulch Lookout Station during the fire season of 1912, had

declined the invitation to serve in 1913, having found a “better paying

job”; and, second, to review the qualifications of three new applicants.

The first applicant,

McCarthy’s letter continued, was a man “whose reputation for the various

cardinal virtues that go to make up a desirable employee of Uncle Sam’s

is not of the best: It’s liable to ‘run’ in warm weather.” Concluded

McCarthy, “I could not conscientiously recommend him, even in a

‘pinch’.”

The second applicant,

wrote McCarthy, was:

…a passably good fellow…whose eyesight is

reported to be not of the best, but who is also said to be one of the

best rifle shots in the country, he having shot more holes in game laws

than any other man on the Salmon…For various other reasons…I should

prefer to defer recommending this applicant until I had to.

“The third applicant

is also ‘no gentleman,’” continued McCarthy:

…but has all the requisites of a

first-class Lookout…The novelty of the proposition which has been

unloaded upon me, and which I am now endeavoring to pass up to you, may

perhaps take your breath away, and I hope your heart is strong enough to

stand the shock. It is this: One of the most untiring and enthusiastic

applicants which I have for the position is Miss Hallie Morse Daggett,

a wide-awake woman of 30 years, who knows and has traversed every

trail on the Salmon River watershed, and is thoroughly familiar with

every foot of the District. She is an ardent advocate of the Forest

Service, and seeks the position in evident good faith, and gives her

solemn assurance that she will stay with her post faithfully until she

is recalled. She is absolutely devoid of the timidity which is

ordinarily associated with her sex as she is not afraid of anything that

walks, creeps, or flies. She is a perfect lady in every respect, and

her qualifications for the position are vouched for by all who know of

her aspirations.

In his letter,

McCarthy asked his supervisor if Miss Daggett’s sex would bar her from

the position. He ended his letter with a conscientious recommendation

that they try “the novel experiment of a woman Lookout.” McCarthy’s

thought was that setting such a precedent would not be likely to cause

future embarrassment “since we can hardly expect these positions to ever

become very popular with the Fair Sex….” Little did they know the time

would come when it would be rare to find a male Forest Lookout!

Miss Daggett’s

application was quickly approved. McCarthy submitted the appointment

papers on May 26, 1913, recommending Miss Daggett as a “Forest Guard” at

a salary of $840 per year. Included with the letter was an Oath of

Office statement, Personal Statement sheets, and the words “Miss Daggett

will take charge of the Eddy’s Gulch Lookout Station.” And so she did.

Hallie went to work on June 1, 1913, and returned each June for the

four-to-seven-month tour of duty for the next 15 years. During those

many years, newspapers across the nation, from the Boston Globe

and the Christian Science Monitor to the San Francisco Call,

had headlines reading “She Guards from Fires Great Timber Area of the

Salmon River Shed,” “Withal, First Woman Fire Warden is Very Feminine

and Also Quite Efficient,” “Female Ranger Watches Salmon River Forests,”

“lonely Forest Post Guarded by Woman,” “Woman Forest Guard Kills Bears,

Wildcats and Three Coyotes,” “The Only Woman Forest Fire Lookout,”

“Woman Takes Lonely Post,” Girl’s Lonely Vigil in Forest,” “Woman Keeps

Fire Vigil in Siskiyous,” etc. Never were the fires on the Salmon River

Watershed reported more quickly, it was said.

In November 1920, a

Mr. M.F. Bosworth of Cleveland, Ohio wrote Hallie requesting that she

write him about her unusual occupation atop Klamath Peak. He wished to

include a story about Forest Service stations. There is no record that

Hallie responded to these requests, but it is recorded that on her

off-season trips to Los Angeles and San Francisco to visit friends she

spoke before numerous women’s clubs on Forest Service activities. Her

audiences, mainly female, were always deeply interested in her own life

on the Lookout. They admired her independent spirit and many, no doubt,

would have been glad to change places with her.

In August 1917, Hallie

received a telegram from Robert A. Bracket, who worked with C.L.

Chester, Inc., Motion Picture Producers of New York. It read, “We are

desirous of making motion pictures of you and your work, showing what

you do and how you do it together with beautiful scenery and sufficient

action to make it of interest. Please write immediately.” On August 14

Hallie responded that she had taken the matter up with the office and

the Forest Service would be pleased “to have you take the motion

pictures you suggest, and will gladly furnish you with any assistance

and action you may need….”

The scenery, I think, you will find very

satisfactory. I would suggest, however, that you time your coming on or

after September 1st as the country is at present too smokey

to secure good results.

It is not know at this

time of writing if the film was made.

A Hollister,

California reporter once asked Hallie how she passed her time. “Do you

read?” he asked.

“I get some time to

read, but mostly I’m on the lookout for fires,” she replied. “There are

other stations in the forest and the men on duty are constantly on

watch. The station that reports the most fires and reports them first

gets the most commendation in the report of the Forest Supervisor. Of

course that keeps us all on the alert.” She had a deck of cards and

would play solitaire, although, as she said, she “kept alert.”

Hallie did not court

publicity, but all who heard her speak or read about her knew she was

deeply in earnest about her work and felt herself an integral part of

forest conservation and the inheritance she was helping to guard for

future generations to enjoy. She fully supported the government’s policy

of saving the forests from fire destruction and “the axe of the timber

grabber.”

Tall, strong, and

sunburned, with a breezy air that identified her as an outdoor dweller,

Hallie had sprung from pioneer parents. Her father, John Daggett, a

tall, intelligent, distinguished-looking gentleman, born in New York on

May 9, 1833, had crossed over the Isthmus of Panama in June 1852 in

search of the goldfields. Later, he was to note his occupations as

“miner, politician.” He was a Democrat and a Mason. He had made his way

to Klamath County from Los Angeles and San Francisco in 1854. Hallie’s

mother, Alice Pamelia Foree, born in Hannibal, Missouri in 1849, had

been brought west across the plains in a party captained by her father,

William Green Foree. Foree ultimately owned a Spanish land grant in Vaca

Valley, and Alice was educated in Vacaville and San Francisco. Pioneer

records indicate that she arrived in Klamath County in 1863. Seven years

later, she met, and on December 17, 1870 married, John Daggett at Black

Bear; he was 37 and she was 21. They had six children: Fen F., Hallie

M., and Leslie W.; three other children died young.

John, at the time, was

part owner and superintendent of the Black Bear Mine, so named because

of the many black bears seen in the forest nearby, near Sawyer’s Bar,

California. It was said that he had already taken two fortunes from the

mine and was sure there was yet a third. A popular and increasingly

prominent man, Mr. Daggett had been elected to the state assembly where

he served four years (1882-1886). He then became Lieutenant Governor of

California, a position he held for two years. In 1891 he served as one

of the commissioners at the Chicago World’s Fair. Following this he

became superintendent of the U.S. Mint in San Francisco.

Hallie and her sister,

Leslie, were accomplished and refined young women, having completed

courses at girls’ seminaries in Alameda and San Francisco. But both had

a deep love for their childhood home near the Black Bear Mine not far

from the town of Sawyer’s Bar in the Salmon River Drainage. With their

brother, Ben, they had explored many of the trails in the rugged

Siskiyous. All had learned to hunt, ride, fish and shoot early in life.

Hallie was especially adept at trapping, and she was an expert rifle

shot. She had no fear of bears, coyotes and wildcats; nor did she fear

anything else in her rugged world, including the frequent electrical

storms she endured on her mountaintop. Why should she? She had a

telephone beside her, and when the thunder would permit, she would call

Ranger McCarthy to report all was well.

“Weren’t you

frightened?” he would ask.

“Why, no!” came back

her cheerful response. “It was exciting while it lasted, and I love to

watch the display. It was simply grand!”

About such storms,

Hallie once wrote,

…There seems to be very little actual

danger from these storms, in spite of the fact that they are very heavy

and numerous at that elevation. One soon becomes accustomed to the

racket. But their chief interest to the lookout lies in the possibility

of their starting fires, for it requires a quick eye to detect, in among

the rags of fog which arise in their wake, the small puff of smoke which

tells of some tree struck in a burnable spot. Generally, it shows at

once. But in one instance there was a lapse of nearly two weeks before

the fall of the smoldering top fanned up enough smoke to be seen.

Hallie concurred with

those who believed the electrical storms responsible for most of the

forest fires, “as traveler and citizen alike are daily feeling more

responsibility for the preservation of the riches bestowed by nature.”

The general trend of opinion at the time seemed to be that the Forest

Service was “doing an excellent work in keeping a watchful eye on the

limits of that hitherto wholesale clearing.”

Hallie’s telephone,

which kept her in touch daily with her local world, “…with its gradually

extending feelers through the district, made me feel exactly like a big

spider in the center of a web, with the fires for flies.” Her dependence

on the telephone she learned one afternoon soon after her arrival on the

forest in 1913 when an “extra heavy” electrical storm broke nearby,

causing one of the lightning-arresters outside the cabin to burn out.

Hallie was cut off from the rest of the world until the next day when

someone from the Sawyer’s Bar Office traveled the nine miles up to the

station to find out the cause of the silence and to see if she was all

right. “They often joke now about expecting to find me hidden under some

log for safety…” But that would have been out of character for Hallie.

Believing one’s

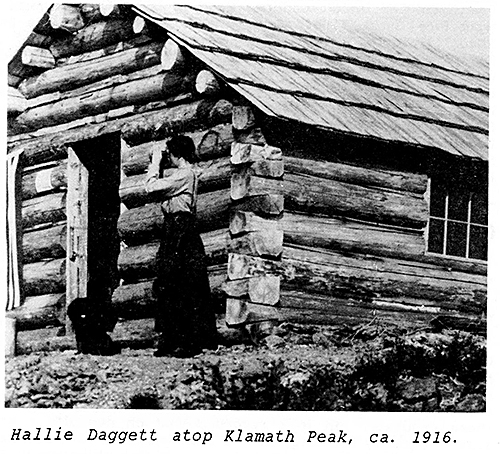

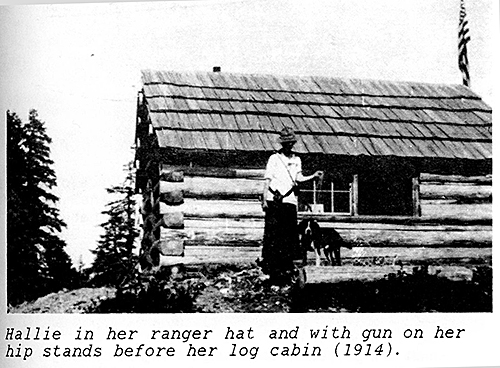

costume should fit the occasion, Hallie most often wore a heavy duty

shirt and knickers for riding to and from her cabin at the beginning and

end of her season. But photos of her at her cabin show her in the

popular ankle-length skirts and pretty, feminine high-necked blouses of

her day. From her second season on, however, it was a rare experience to

see her without a revolver strapped to her belt, ready to be drawn from

its holster at a moment’s notice if danger threatened. She often said

the only thing that really filled her with dismay was contemplating the

end of the fire season, when she would have to leave her “scenic abode:

and return to “the imprisoning habitations of Civilization.”

Though Hallie was

ready to protect her life from marauding wild animals, she turned with

gentleness to the smaller animals and birds as they clustered around her

cabin. She once wrote how plentiful bird and animal life was: “They

filled the air with songs and chatter, coming to the door-step for food,

and often invading the cabin itself.”

…I positively declined owning a cat on

account of its destructive intentions on small life—a pair of owls

proving satisfactory as mouse-catchers, and being amusing neighbors as

well…Several deer often fed around evenings, and I put out salt for

them. There was a small brown bear near the spring, besides several

larger ones whose tracks I often saw on the trail. A couple porcupines

kept me from being lonesome by using various means to find a way into

the cabin at night, mainly at the window sills. Grouse and quail raise

their young around my cabin door. One summer I had seven pet chipmunks

eating out of my hand. I raised one little waif on condensed milk, and

later he would raid my pockets for corn and biscuit. All these animals

being harmless, it had never been my custom to carry a gun in so-called

Western fashion, until one morning I discovered a big panther track out

on the Trail, and then in deference to my family’s united request, I

buckled on the orthodox weapon which had been accumulating dust on the

cabin shelf and proceeded to be picturesque. But to no avail, as the

beast did not again return.

During the 1915

season, however, Hallie killed one bear, four wildcats and three

coyotes. At that time the county paid a bounty on all but bears.

The small cabin Hallie

called home close to half the year had been built of rough-hewn logs

atop 6,444-foot Klamath Peak during the summer of 1912.

I’d never thought of [Klamath Peak] as a

possible home. One of my pet dreams had always ben of a log cabin, and

here was an ideal one—brand new the summer before, and indoors as cozy

as could be wished, while outdoors —all outdoors—was a grander dooryard

than any estate in the land could boast, and oh! what a prospect of

glorious freedom from four walls and a time-clock.

Though news and

magazine writers insisted on calling her vigil on one of the loftiest

peaks of the Salmon Summit “lonely,” to Hallie it was anything but. “It

was,” she admitted, “quite a swift change from San Francisco,

civilization and sea-level, to a solitary cabin on a solitary peak, on a

still more solitary mountain a mile and a quarter above sea-level.” But

she never felt a longing to retrace the step—“that is, not after the

first half-hour following my sister’s departure with the pack animals,

when I had a chance to look around.”

Lonely? Never. There

was the “ever-busy phone with its numerous calls.” And sister Leslie

brought supplies, newspapers, and mail from home every week—a distance

of nine miles and “a good three-hour climb from everywhere.” There were

visitors, too, “guards who passed that way” as well as hunters,

prospectors, and campers, so Hallie kept the kettle boiling. And there

was always the great map spread out at her feet so that she might study

“by new lights and shadows while waiting.” Though photos show the

frequent presence of a dog, it is thought that one may have accompanied

Leslie on her weekly trips to Klamath Peak. “I have no need for a dog,”

Hallie once said, “as anything or anyone approaching can be easily seen

and heard.” Despite her wish not to have a cat, she wrote in 1916 that

she had a pet kitten “who helps to answer the phone and is as well a

good ‘watchdog’.”

Perhaps the most

rewarding of all was the time she spent viewing through telescope (later

“field glasses”) the magnificent, rugged Siskiyou Mountains about her.

…Klamath Peak is not really a peak in the

conventional sense of the word, but is rather the culmination of a long

series of ridges running up from the watershed of the north and south

forks of the Salmon River. Its central location in the district makes

it…an ideal spot for a station. I can think of no better description of

it than the hub of a wheel, with the lines and ridges as spokes, and an

unbroken rim of peaks circling around it. Some eternally snow-capped,

and most of them higher than itself.

From her peak, Hallie

could view 14,162-foot magnificent Mt. Shasta to the east and the

Pacific Ocean to the west, and the grand sweep of country in between. It

made up what was said to be one of the finest continuous views in the

West. She would see a neighboring lookout on Eagle Peak; farther to the

south there was the high jagged edge of Trinity County, and just

discernible with her powerful glasses, a shining new cabin on Packer’s

Peak. To the west, behind Orleans Mountain “with its ever-watchful

occupant,” Hallie could, with a favorable sunset, catch a faint glimpse

of the shining Pacific, and all in between, a “seeming wilderness of

ridges and gulches and pine-, cedar- and fir-lined canyons. It was

certainly a never-ending pleasure to search its vast acres for new

beauties at every changing hour from sunrise to sunrise again.” Hallie,

it must be remembered, was on 24-hour duty daily. She loved the

“constantly spreading fairy-tinted carpet of wildflowers to the very

edges of the snow-banks.” She had them all summer, followed by “the

gorgeous autumn coloring on the hillsides…when the whole country seemed

one vast Persian rug.”

She was determined to

do her duties faithfully. She had to make good, “…for I knew that

the appointment of a woman was rather in the nature of an experiment,

and naturally felt that there was a great deal due the men who had been

willing to give me the chance.” Her major duty was to “scan the vast

forest in every direction as far as I could see by naked eye and

telescope by day, for smoke, and the red glare of the fire at night.”

Then she was to report her observations by telephone to the main office

of the forest patrol at Sawyer’s Bar.

Hallie herself thought

of her other duties “on top” as small,

…merely consisting of an early morning and

late evening tramp of half a mile to the point of the ridge where the

trees obscured the north view from the cabin, and a constant watch on

all sides for a trace of smoke.

She raised and lowered

the flag daily, a ceremony she took quite seriously. In the earliest

days it was tacked to the logs at the front of her 12 x 14 ft. cabin.

Hallie soon came to

feel that the Lookout was indeed “an ounce of prevention, “as one of her

friends apty called it. Hallie reported three times daily to the

district headquarters “to prove that everything was serene.” An

occasional extra report was made if she had spotted a puff of smoke

somewhere on her forest. And there was “a little—very little—housework

to do.” Hallie would be the fist to admit that, all in all, her days

were not very busy as judged by “…modern standards of rush. But the the

Lookout motto might well be, ‘They also serve who only stand and wait.’”

Hallie had been born

at Klamath Mine in the shadow of the peak on which her Lookout station

was perched. She wrote,

My earliest recollections of that first

season abound with smoke-clouded days in summer, and fires that wandered

over the country at their own sweet will, unchecked, unless they

happened to interfere seriously with someone’s cabin or woodpile, when

they were usually turned off by back-firing and headed in another

direction, to continue at their mischief till they either died for lack

of fuel, or were quenched by the fall rains. Such being the case, it is

easy to see that I grew up with a fierce hatred of the devastating

fires, and welcomed the force which arrived to combat them. But not

until the lookout stations were installed did there come an opportunity

to join what had up till then been a man’s fight, although my sister and

I had frequently been able to help on the small things, such as

extinguishing spreading campfires, or carrying supplies to the firing

line.

Hallie added, the

fires were often discovered at night “when they look like red stars in

the blue-black background of moonless nights.

Because of the high

elevation, the question of wood and water was a serious one—this was

true of most of the stations in the second decade of the twentieth

century. “But I was especially favored,” Hallie wrote, “as wood lies

about in all shapes and quantities, only waiting for the axe to convert

it into suitable lengths.” And Hallie could wield an axe. Water was

unlimited, for Hallie was surrounded by snowbanks as late as the end of

July, “although it did seem a little odd to go for water with a shovel

in addition to a bucket.” Later, she was to pack in canvas sacks from a

spring about a mile away in the timber.

In her first season

(1913), Hallie reported some40 fires and was praised by Ranger McCarthy

for her promptness. Out of that number of fires, fewer than five acres

were burned, McCarthy wrote, “due entirely to the fact that rangers and

guards had such prompt warning that suppressive efforts wre put forth

before the fires could gain an appreciable headway. Had one less

faithful been on the Lookout, it might easily have been five thousand.

The first woman guardian of the National Forests is one, big, glorious

success.”

Wrote Hallie,

…Fires were certainly treated to exactly

the speedy fate of the other unworthy pests. Through all the days up to

the close of the term on November 6, when a light fall of snow put an

end to all danger of fires, there was an ever-growing sense of

responsibility which finally came to be almost a feeling of

proprietorship, resulting in the desire to punish anyone careless enough

to set fires in my dooryard.

Hallie could become as

irate at those careless about fire in her forest as Carrie Nation had

been a generation earlier at those irresponsible about alcohol. In 1915,

75 people and countless forest animals across the nation had lost their

lives in forest fires. The dollar cost to the nation’s forests that year

had run about $25 million.

Hallie’s vacation time

was two days off each month,

…With this respite, the work never grows

monotonous. My interest is kept up by the feeling of doing something for

my country—for the protection and conservation of these great forests is

truly a pressing need. To women who love the ballroom and the glitter of

city life, this work would never appeal, but to me it is work more than

useful—it is a grand and glorious vacation-outing, for the very

lifeblood of these great foliated mountains surges through my veins. I

like it; I love it! And that’s why I’m here.

An article in the

Siskiyou News in October 1916 noted that the women of the summer

protective force fared better than the men as they were still on duty.

Named were Hallie, of Sawyer’s Bar, and the telephone operators whose

alertness helped her play a vital part in the fire suppression work:

Mrs. E.A. Smith, Walker; Mrs. J.B. Johnston, Hamburg; and Mrs. Gorham

Humphreys, Happy Camp. The same news writer, carried away by visions of

Hallie’s expertise, raved on. “Looking ten years into the future,” he

wrote, “it is very probably that the Forest Service notes will contain a

paragraph as follows:

Last Saturday at noon a fire was sighted

about 70 miles west of Etna by Miss Daggett, aeroscout, in her biplane.

The location of the fires was immediately reported to headquarters at

Yreka by wireless telephone. Forest Supervisor Rider ordered out Forest

Service zeppelin No. 2 from Ranger Gott’s hangar with a crew of men.

With the zeppelin piloted by Master Mechanic William Groom, they were

over the fire in one hour, and with the new chemical apparatus, had it

under control after it had burned over a half-acre of timberland. This

is the largest fire the service has had in two years. The tourists who

left the campfire which did the damage were sighted by Aeroscout Daggett

speeding westward in their automobile over the Salmon River boulevard.

They were overtaken at Orleans and taken before the U.S. Commissioner at

Redding, who imposed a fine of $5,000 and treated them to a severe

reprimand.

That didn’t

quite come to pass, but by 1917 Hallie did have an instrument attached

to a new map which helped her locate the exact spot where smoke was

rising. By 1918, U.S. involvement in World War I as beginning to deplete

the forest lookout stations of manpower, and Hallie was no longer

the sole woman forest guard in the nation. Two others, including

23-year-old Miss Mollie Ingoldsby on California’s Plumas National

Forest, had been added to the service.

In 1927, after 15

years of faithful service, Hallie Morse Daggett retired to her

homestead, Blue Ridge Ranch, some 10 miles from Eddy’s Gulch, where she

continued to raise the American flag each fair day.

Rosemary Holsinger,

born in Los Angeles, received an M.A. in Education from Stanford

University. She taught at Santa Clara University, among other places.

She moved to the Siskiyou Mountains in northern California in the

1970s. She was interested in helping to preserve local history. Her

house in Etna was situated on a lot in front of two houses once occupied

by the Daggett sisters after Hallie left her Blue Ridge Ranch homestead

in late years to be near sister Leslie.