Tambomachay

"...The ninth [holy place] was

named Tambomachay; it was a house of Inca Yupanpui where he lodged when

he went hunting." Bernabe Cobo, 1653.

"...that city of Cuzco was house

and dwelling of gods, and thus there was not, in all of it, a fountain

or passage or wall which they did not say held mystery." Juan Polo

de Ondegardo, 1571

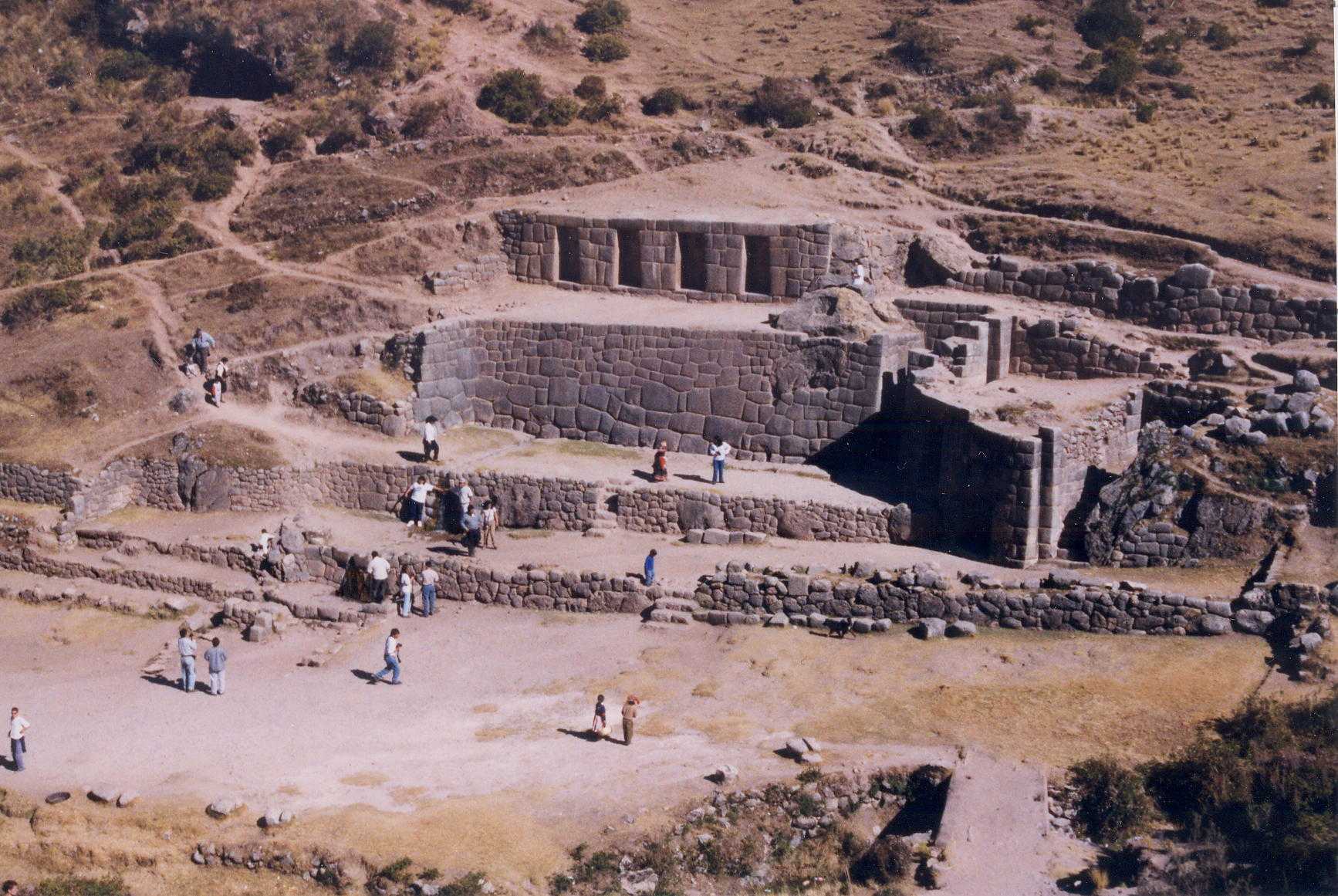

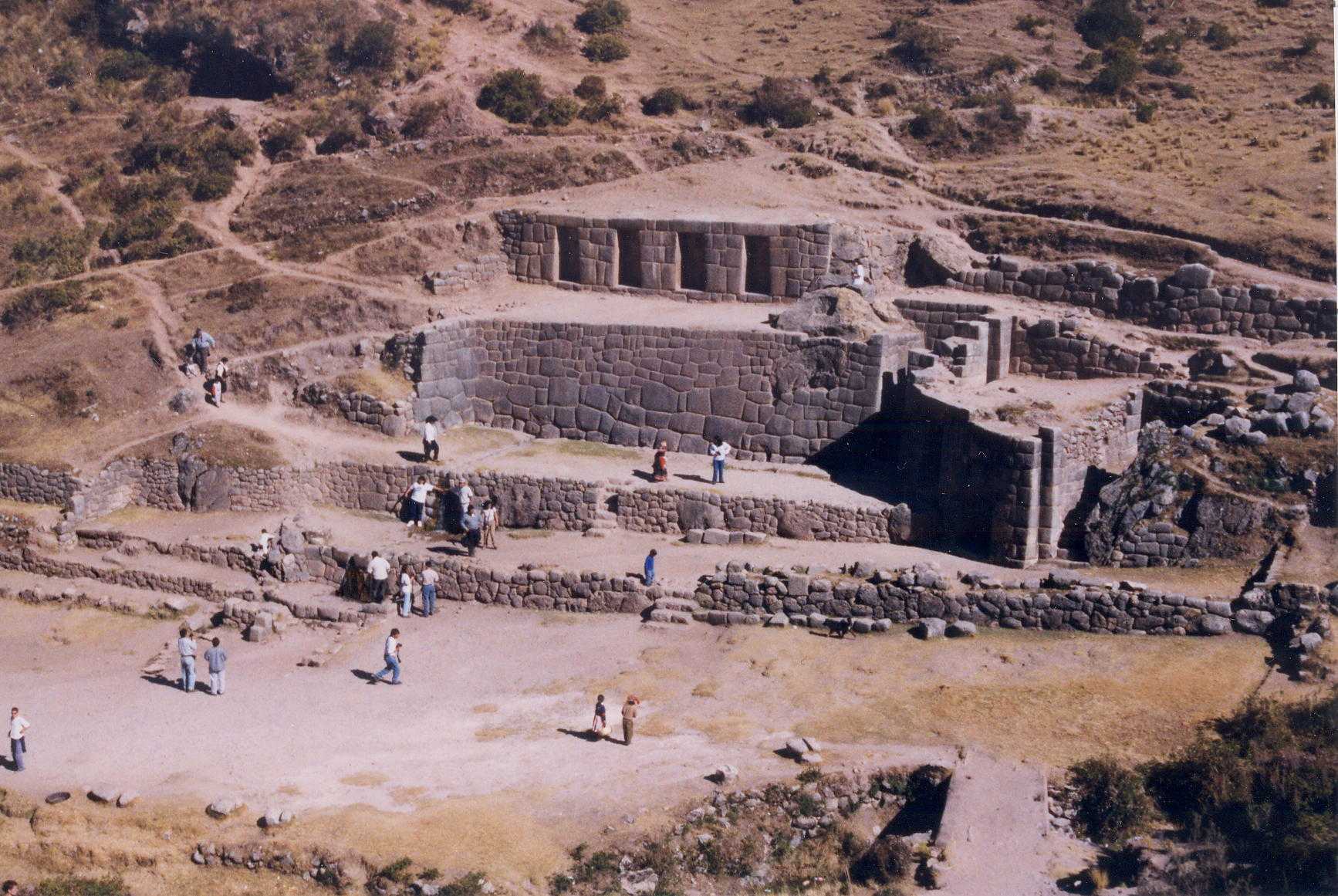

The archaeological site of Tambomachay is located about 8 km north

of the city of Cuzco, in the southern Peruvian highlands. The well-crafted

stonework, beautiful fountains, and pastoral setting on the Cachimayu ("Salt

River") combine with ease of access to make this site one of the most visited

in the area.

| High quaility stonework, a double-jam doorway, and the four large,

outward-facing niches all indicate that the site was an important shrine

to the Incas. Despite the importance of the site to the Incas, the

original name is uncertain. Cobo (1653) tells us that Tambomachay

was a house (see reference above), and there is no provision for lodging

at the present day archaeological site. It is likely that the original

name was "Quinoapuquiu". Cobo tells us that Quinoapuquiu "...was

a fountain near Tambo Machay which consists of two springs." |

|

|

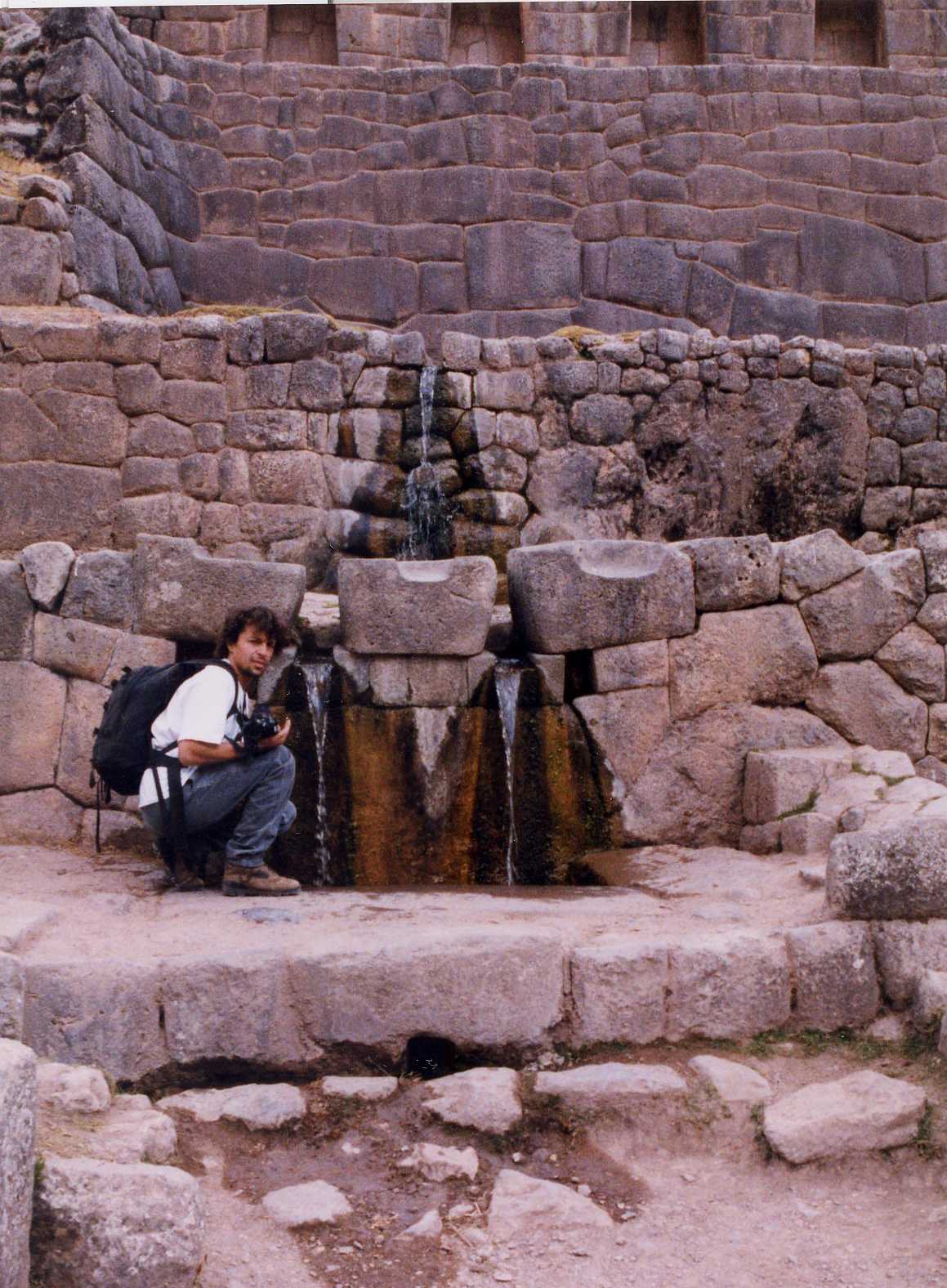

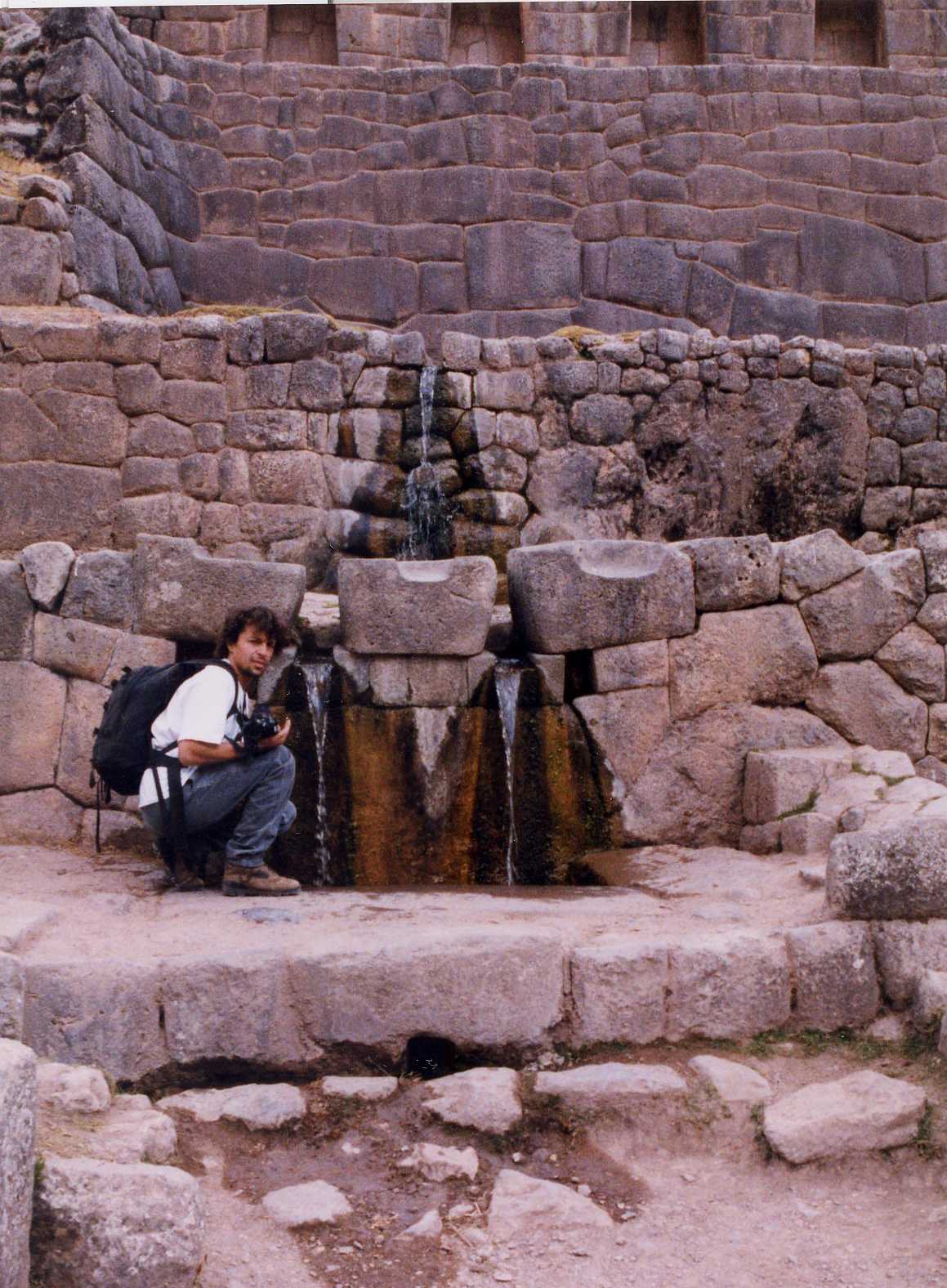

These beautiful fountains are the focal point of the site.

Set slightly off-center, the fountains make a dynamic architectural composition

that underscores the importance of the spring. The area around Cuzco

receives a yearly average of 950mm of rainfall, mostly during the few months

of monsoon season. In this semi-arid region, the spiritual treatment

of the spring is in harmony with the importance of a dependable water supply. |

| The hydrologic nature of the site captured my interest during a

visit in 1995. Since that time I have been studying the hydrogeology

of Tambomachay and other Inca sites. Understanding Inca water

management practices requires a knowledge of Inca culture, as well as a

good background in hydraulics and geology. The happy result is the

opportunity for archaeologists and hydrologists to work together and learn

from each other. Archaeohydrology, is a true multi-disciplinary area

of study. |

|

|

The image to the left shows the interaction between the groundwater

and the Inca construction. A ridge of limestone bedrock blocks groundwater

from flowing to the river (right edge of photo); a similar ridge blocks

the water on the other side of the stone walls (not visible in this photo).

The stone construction is located so as to control the discharge of groundwater

through the gap between the two limestone ridges. The Cachimayu is

dry in the foreground of the photo; however, some water is underflowing

the

walls, and can be seen discharging to the riverbed near the bridge (left

center). The walls filter and collect the groundwater, and may slow

the discharge to store water in-situ in the earth behind the walls. |

The work I have been doing at Tambomachay has only been possible

thanks to the generous funding provided by the Stahl Foundation,

and by the Earth Sciences Division of Lawrence Berkeley National

Laboratory. If you are interested in learning more about my

work at Tambomachay and other Inca sites, you can wait for my publication

in Latin American Antiquity (currently in review), or E-mail me at: jfairley@uidaho.edu.