Originally published in Women in Forestry, Winter 1985-86, 7(4):

21-23.

The sun

marked midday in the high country of Wyoming’s Wind River Range. We’d

been hiking all morning, and as my stomach growled, I surveyed

constantly for something to eat. Two of my companions, Bob and Cindy,

were kneeling in a clearing and digging excitedly. “Look what we

found!” Cindy called. “Wild chives!”

After 18

hours without food, a strong onion wasn’t exactly what I wanted, but I

knelt and joined the feast, munching flowers and all.

My

friends and I had just embarked upon a ten-day trek with five goats and

no food. The goats would carry our gear, and we would forage alongside

them.

One day

earlier, when my friend John Mionczynski, a naturalist (and accordion

player), had asked me to join the expedition, I admitted I was scared.

Although I enjoyed collecting plants to eat or study, I’d never gone ten

days without “real food.” And while my work for the Bureau of Land

Management—fencing a ghost town and caring for campgrounds—kept me fit

and active, I didn’t know John’s other friends and was afraid I’d hold

them back. “So is everyone else afraid,” he assured me, “only they’ve

been worrying a lot longer than you have!”

We

loaded John’s goats in the truck, started off, and waved to neighbors in

Atlantic City, Wyoming. In this town of about 50 cabins and 1870s gold

fame, the old mining days are kept alive. A few residents still work

claims; others have cottage industries—like John, who makes goat-packing

gear. So, in keeping with the region’s pioneer spirit, we set off.

My other

companions, all in their mid- to late-thirties, had high expectations.

Roy Ozanne, who studies mice (and yoga) in Wisconsin, first thought of

this trip. He wanted to be in the alpine on nature’s terms. Jeff

Springett, a carpenter from Alaska and Wyoming, planned to hike to a

glacier, as evidenced by the ice ax on his pack. Cindy Day, who sells

herbs in the Teton Valley, wanted to cleanse her body with a diet of

pure mountain food.

When I

was growing up in the hills of West Virginia, I spent much time outdoors

and often collected wild nuts and berries. Then as a teenager, I began

experimenting with other wild edibles and took a botany class to better

identify the plants. So at age 21, this trip was a great way for me to

combine my life-long fascinations with wildlands and native flora.

I

wondered if this would be a big change for another companion, Bob

Rountree, a doctor from Colorado who usually worked long hours and drank

a lot of coffee. We were all fit, but I suspected the mental adjustment

might be greater than the physical one. None of us realized just how

difficult it would be.

Packing

goats was also a first for most of us. One morning over our breakfast

tea of spruce needles (for vitamin C and energy), yarrow flowers (to

balance out body functions), and rose hips (for almond flavor), John

told us how he got started: “In 1972, I had too much gear to haul while

tracking bighorn sheep as a Forest Service wildlife technician. My

horses couldn’t get around the rough terrain, so I packed the 125 pounds

of equipment. After falling into a torrential river, then struggling up

a steep mountain as my sheep disappeared, it was clear I needed help. I

went home to get my goat and try out an idea. I fashioned a saddle from

scrap wood and broom handles, but it broke apart. So I built another

rone which I still use. That summer I packed two goats and carried a

knapsack—it worked beautifully and I’ve done it ever since!”

My

friend, lean and lively with bright brown eyes, looked agile enough to

be part goat himself. As far as I can tell, he invented goat packing in

North America. A brilliant idea, I thought, as our pile of gear

mushroomed.

We

packed the gear (including oil and spices to make the plants more

palatable), in canvas bags (called panniers), which Kate Bressler had

sewn. “Cattle Kate” is a seamstress who lived in Atlantic City ten

years ago and who used a treadle machine there. Now she makes period

clothing in Jackson. She and John were the only members of our group

who had packed with goats.

We

learned quickly about fitting cinches and loading the animals. Each

goat had a special rig and a specific amount of weight to carry. Tin

Cup, the largest male, stood as tall as an antelope. Not yet

full-grown, he could haul 70 pounds. Brownie, a youngster on his first

trip, was packed with light unbreakables. When Jeff saddled Brownie,

the goat dashed off to lose that strange thing clinging to his back. He

galloped around, then charged his brothers while still fully packed.

Pans and sleeping bags went flying. We scrambled as the goat headed

straight toward us. When Brownie decided he couldn’t outrun the saddle,

Jeff slipped on the panniers. The little guy took off with a buck and a

bawl. More reckless dashing and sailing gear followed. Goat packing is

a pioneering way to travel for both goats and people!

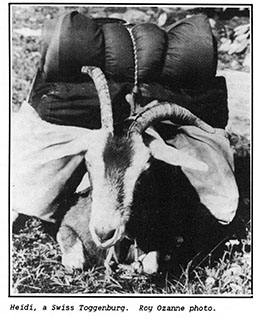

As John

led the oldest goat, Heidi, up the trail, the others fell into line.

Brownie stayed on his mother’s heels and Tin Cup followed. Bekins was

next, and Jupiter brought up the rear.

While we

hiked, we looked continually for plants to snack on or to collect for

supper. Shortly after our feast of wild onions, we came to a meadow

where ribbons of water cut a far timbered slope and wound down past us.

I hacked at a few prickly thistles which dotted the field. Although

some people know thistles only as weeds, their crunchy inner stems make

a pleasant treat.

That

evening, our supper consisted of stew and salad—bluebells, fireweed,

pigweed, wild buckwheat, chives, and other greens we’d gathered while

hiking. After studying my salad and relishing each crisp bite, I then

dipped hesitantly into the pot simmering on the fire. One small cup of

the slimy, brownish-green stew was enough for me. But Roy enjoyed his

and went back for more. In coming days, he would always rave about our

concoctions. The rest of us sometimes just gagged them down.

Next

morning I was glad I’d only tasted the stew. John and Roy had stomach

aches and didn’t feel very chipper. John thought one of us might have

dropped poisonous Arnica in the pot, mistaking it for bluebell.

“From now on,” he said, “I’ll check everything that goes into our

dinners.” In those early days, we all felt lethargic. Later, our

energy returned.

The

rough trail snaked across steep talus slopes, and we stopped often to

lounge in the sun or look at plants. John knew a use for nearly

everything we saw: Arnica, though toxic when eaten, can be used

topically to kill pain; green juniper berries boiled in water make a

hair rinse to cure dry itchy scalp, and alumroot, which grows on rock

outcrops, is a strong astringent.

John’s

lessons occupied us and we never tired of the strengthening sight of

rugged mountains. The days slipped by. One day, we crested the highest

peak on our trip and descended to Goat Flat, a dry, barren plateau. I’d

been collecting greens earlier, including my favorite, tangy mountain

sorrel, but didn’t see much here to fill us up. Yet on these treeless

slopes, we would discover several special foods. Jeff and Roy found

puffballs—large white fungi without stems. After spying bistort around

us, I grabbed my trowel and went to work. The pinkish-white root knobs

of bistort grew about five inches deep in the gravelly soil. Although

my fingers ached digging them out, it was well worth the trouble. We

sautéed the nut-flavored roots of bistort with puffballs for a fireside

delicacy. As I curled up under a gnarled fir for the night, my stomach

full of bistort, I thought it was the best meal I’d ever had.

Four

days into the trek, we decided to give the goats a rest and make a side

trip to find biscuitroot, a starchy carrot. Bob, Cindy, and Kate wanted

to fish in a lake nearby. So we sneaked away from the goats to search

for supper. We labored up rocky summits to find puffballs and

magnificent views, but no biscuitroot was found.

We

explored a krumholz made up of dwarfed pines on the lee side of a

mountain that must have been the site of an old Sheepeater Indian camp.

Flint chips from tool-making littered the ground, and a medicine

turtle—a ring of stones shaped like turtle—watched over the Indian’s

homeland. Afternoon brought frigid rain and eerie mist, and as I

shivered in the krumholz, I imagined the long-ago Indian families

seeking protection there, too.

We also

spied on some bighorn sheep. Unfortunately for the other women, who

felt very weak, it was not our day to find biscuitroot.

Cindy

caught a trout that went in the stew pot. She and Kate made a stunning

flower salad of white columbine, purple hairbell, red paintbrush,

rosecrown, and miners lettuce. The salad, stew, and dandelion tea put

new fire in my muscles, and my body felt cleansed and strong. I was

ready to go on like this all summer.

By the

time the fellows were ready to go next morning, I felt like flying up

the mountain. I knew we’d find lots of energizing food, then head out

toward Jeff’s glacier the next day. We wished the anglers luck.

Our

energy subsided a bit on the first ¾-mile slope; we weren’t in a hurry

and took time to study the plants. We climbed high above the trees to a

saddle where we’d seen bighorns and fanned out to hunt for the elusive

biscuitroot. Finally John called to us. He made a few triumphant jabs

with his trowel, then help up a lacy-leaved plant with a thick root—the

reward of a long climb and a two-day search. We all dropped to our

knees on the windy ridge and began digging furiously. After four days

of surviving on little but greens, this starchy plant would lift us to a

new energy level.

Kate and

Cindy had hooked one tiny fish. It was less than four inches long, but

they fried it and ate it, bones and all. I knew they were getting

desperate for energy food, and I worried that biscuitroot wouldn’t be

enough. They confirmed my fears that afternoon. As we huddled by the

fire, Kate said, “We can’t enjoy the trip when we’re so weak, and we

don’t want to hold you all back. So Cindy and I will hike out

tomorrow.”

This

seemed acceptable to me, but others were more thoughtful If these two

left now, the whole experience would be a defeat for them. We decided

to hike where fishing might be better, instead of to the glacier, and to

cut our trip two days short.

On the

seventh day we started hiking out, just when our spirits were picking

up. “That’s how it works,” John told me. “Your energy wanes at first,

then surges as your body adapts.” Our energy WAS surging; we hiked all

day, hardly stopping to pick a puffball.

That

last night I slept in a meadow lighted by a large moon and rose to frost

and a magnificent view of the southern Absaroka range. None of us had

anticipated how relaxed we had become, nor the special bond we had

developed with the land. It was hard to leave this place. But we

loaded the goats early, waited for Roy to get up, and took off down the

mountain.

The

trail out was steep and rocky with many switchbacks. Bekins tried to

shortcut every turn; Tin Cup and Brownie were worn out and had to be

coaxed through the last few miles. My own back and knees ached.

We had

thrived on clean mountain food for the past eight days. But by the time

the trailhead was reached, everyone had one thing in mind. Bob voiced

it first: “Let’s go to a deli!”

Lynn

Kinter received her degree in Wildland Recreation Management from the

University of Idaho in 1986.