|

Nothing But the Truth

American Indian Non Fiction

·

20th century Native non-fiction is a continuation of 2

centuries of a tradition of nonfiction protest literature. - Samson Occom

(Mohegan) 1772 sermon

William Appess (Pequot), 1883: "The Indian's Looking Glass for the

White Man"

* Contemporary writers have concerns with postmodernism,

nationalism, humor, the Ghost Dance, language and imagination, authenticity and

identity, the power of stories

·

NA writers blur “European” categories or genres

·

We read simultaneously of ethics and aesthetics, politics and

poetry, history and myth, identity and community

Brian Swann

Introduction: Only the

Beginning

End of the Trail, James Fraser, from The Vanishing American

End of the Trail, James Fraser, from The Vanishing American

transculturation:

A term coined by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz that refers

to a process in which "members of subordinated or marginal groups select and

invent from materials transmitted by a dominant culture." Transculturation

emphasizes the agency involved in cultural change, as well as the loss that

accompanies cultural acquisition. In these ways, "transculturation" differs from

the older terms "assimilation" and "acculturation," which emphasize a more

one-way transmission of culture from the colonizer to the colonized, from the

dominant to the marginalized. For Ortiz, transculturation was a necessary

concept for understanding Cuban and Spanish American culture more generally.

Swann says we have yet to “discover America” because we haven’t looked

at our history or really met Native Americans. Reading AI lit is a way to

“discover America.”

·

AI lit/poetry is literature of Historic Witness

·

A past that is in the present

·

The NA poet is his or her history with all its ambiguities and

complications;

·

Their history is not something external to be learned, molded

or ignored, though it may be something has to be acknowledged and recovered. It

is embodied and unavoidable because the weight and consequences of that history

make up the continuum of the present. This fact gives an urgency to the

utterance, a resonance to the art that carries it deeper than much of the poetry

one finds today. The poets are still “singing for power.”

·

The Native American poet seems to work from a sense of social

responsibility to the group a much as from an intense individuality.

·

Many Native poets consider themselves as both distinct individual

voices and voices that speak for whatever cannot speak.

Who is a Native American?

“Native Americans are Native Americans if they say they

are, if other Native Americans say they are and accept them, and (possibly) if

the values that are held close and acted upon are values upheld by the various

native peoples who live in the Americas.”

Themes in Native literature

Faith in renewal

Reverence of grandparents and parents

Commitment to orality in the non-oral medium of print

“active immediacy” in print, power of the word

Connection to myth/tribal cosmic stories: the animal

people, the first ones

Balance, reconciliation, healing

Relationality

Communitism (Jace Weaver)

Survivance (Gerald Vizenor)

Paula Gunn Allen (Laguna/Sioux/Lebanese)

The Sacred Hoop: A Contemporary Perspective

“The significance of a literature can be best understood in

terms of the culture from which it springs, and the purpose of literature is

clear only when the readers understand and accepts the assumptions on which the

literature is based.”

·

AI literature is unlike Western lit. because the basic assumptions

about the universe and basic reality are dissimilar;

·

AI lit is never pure self-expression

·

AI lit seeks to bring the individual into the communal and cosmic

·

The Word is alive, sacred

·

All is alive; all things have equal value and are not separate

from God.

“The AI universe is based on dynamic self-esteem, while the

Christian universe is based primarily on a sense of separation and loss. For the

American Indian, the ability of all creatures to share in the process of ongoing

creation makes all things sacred.”

Native lit doesn’t rely on crisis, conflict or resolution for organization; its

significance is determined by its relations to creative empowerment, its

reflection of tribal understandings and its relation to the unitary nature of

reality; that things are related to each other.

Space is spherical and time is cyclical (not linear and

sequential)

Indians see all creatures as relatives;

relationship is

central

2 basic forms of Indian lit: ceremony and myth

Ceremony is a ritual enactment of a specialized perception

of a cosmic relationship, while the myth is a prose record of that

relationship.”

Within this ceremonial context, we can understand

repetition and symbolism in a NA aesthetic.

Purpose of repetition: “to fuse the individual with his or

her fellows the community of people with that of the other kingdoms and this

larger communal with the world beyond this one.”

Repetition also reinforces the theme and serves to focus

the participants’ attention on central concerns while intensifying their

involvement with the enactment.”

·

Symbolism in AI ceremonial literature: a semiotic system different

from the Western dualism of sign and signified.

·

Native symbolism is “not symbolic in the usual sense; that is the

four mountains in the Mountain Chant (of the Navajo) do not stand for something

else. They are those exact mountains perceived psychically, as it were, or

mystically.”

·

The ostensible sign or symbol has value itself as the signified or

symbolized.

AI literature attempts to create or restore harmony and

wholeness.

Leslie Marmon Silko (Laguna Pueblo [New Mexico])

Language and Literature from a Pueblo Indian Perspective

* Pueblo Indian storytelling resembles a spider's web with many threads

radiating from the center, crisscrossing one another. The listener must trust

that meaning will be made.

She tells Laguna Pueblo creation story: Thought Woman (Tse'itsi'nako)

by thinking of her sisters and together with her sisters, thought of everything

that is. In this way, the world was created.

For Pueblo and other Native people, language is

story.

Words have stories attached to them. So narrative is story

within story, the idea that one story is only the beginning of many stories and

the sense that stories never truly end.

Storytelling always includes the audience, the listeners;

the storyteller's role is to draw the story out of the listeners. The

storytelling continues from generation to generation.

We know who we are because of our Creation story in this

place.

One moves from one's identity as a tribal person into clan

identity (Antelope, Badger), and then as a member of an extended family.

Family accounts include positive and negative stories. It

is important to keep track of all these stories: by knowing the stories that

originate in other families, one is able to deal with terrible sorts of things

that might happen within one's own family. If others have endured, so can we.

Stories bring us together; they keep family and clan

together. You learn not to isolate yourself when bad things happen: one does not

recover by oneself.

Pueblo people have never been removed from their land. Our

stories cannot be separated from their geographical locations, from actual

physical places on the land. There is a story connected with every place, every

object in the landscape.

Language has a boundless capacity through storytelling to

bring us together, despite great distances between cultures, despite great

distances in time.

N. Scott Momaday, "The Man Made of Words"

* Concerned with relationship between language and

experience

* We are all made of words

* Our most essential being consists of language

An Indian is an idea which a given man has of himself. It is a moral idea, for

it accounts for how he reacts to others. That idea, in order to be realized,

must be expressed.

Racial memory: awareness of place and history due to verbal tradition

Old woman Ko-sahn-- Momaday imagines himself with her in different time

Power of the imagination

"Once in his life a man ought to concentrate his mind on

the remembered earth, I believe. He ought to give himself up to a particular

landscape in his experience, to look at it from as many angles as he can, to

wonder about it, to dwell upon it. He ought to imagine that he touches it with

his hands at every season and listen to the sounds that are made upon it. He

ought to imagine the creates that are there and all the faintest motions in the

wind. He ought to recollect the glare of noon and all the colors of the dawn and

dusk." (84)

"I am interested in the way that a man looks at a given

landscape and takes possession of it in his blood and brain. For this happens, I

am certain, in the ordinary motion of life. None of us lives apart from the land

entirely; such an isolation is unimaginable. We have sooner or later to come to

terms with the world around us--and I mean especially the physical world; . .

.And we must come to moral terms. There is no alternative, I believe, if we are

to realize and maintain our humanity; for our humanity must consist in part in

the ethical as well as the practical ideal of preservation. And particularly

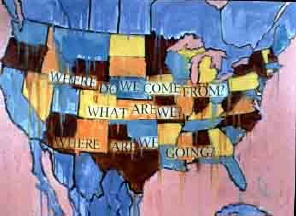

here and now is that true. We Americans need now more than ever before--and in

deed more than we know--to imagine who and what we are with respect to the earth

and sky. I am talking about an act of the imagination essentially , and the

concept of an American land ethic." (86)

"We are what we imagine. Our very existence consists in our

imagination of ourselves. Our best destiny is to imagine, at least,

completely who and what, and that we are. The greatest tragedy is to go

unimagined." 87

"All sorrows can be borne if you put them into a story or

tell a story about them." Isak Dinesen (89).

Simon Ortiz, "Towards a National Indian Literature: Cultural Authenticity in

Nationalism"

What appears to be a Catholic/Spanish celebration is held within

the Acqumeh community it is an Acqumeh ceremony. . . "This is so because this

celebration speaks of the creative ability of Indian people to gather in many

forms of the socio-political colonizing force which beset them and to make these

forms meaningful in their own terms. In fact, it is a celebration of the human

spirit and the Indian struggle for liberation"(120).

Many Christian rituals brought to the SW are no longer

Spanish. They are now Indian because of the creative development that the native

people applied to them. Present-day Native literature is evidence of this in the

very same way.

Because in every case where European culture was cast upon Indian people of this

nation there was similar creative response and development it can be

observed that this was the primary element of a nationalistic impulse to make

use of foreign ritual, ideas, and material in their own--Indian--terms

(121).

It is entirely possible for a people to retain and maintain

their lives through the use of any language. There is not a question of

authenticity here; rather it is the way that Indian people have creatively

responded to forced colonization. And this response has been one of resistance;

there is no clearer word for it than resistance (122)

And it is this literature, based upon continuing resistance,

which has give a particularly nationalist character to the Native American

voice. . . Because of the insistence to keep telling and creating stories,

Indian life continues, and it is this resistance against loss that has made that

life possible. 124.

"Nevertheless . . . the acknowledgement by Indian writers of a

responsibility to advocate for their people's self-government, sovereignty, and

control of land and natural resources; and to look also at racism, political and

economic oppression, sexism, supremacism, and the needless a nd wastetful

exploitation of land and people, . . ." 124.

“Decolonializing

Criticism: Reading Dialectics and Dialogics in Native American Literatures,”

David Moore

Epistemology:

the nature of knowing

There are different

ways of knowing the world

There

are ethical considerations in the aesthetic study of literatures, and

particularly in the study of American Indian literatures due to the history of

colonialism.

·

Colonial cognitive structures

underlie cultural definitions of race and ethnicity, embedded as those

definitions are in the economics of colonial history (94)

·

Moore traces ways in which epistemology is linked to ethics and to

aesthetic study by dualistic, dialectic and dialogic ways of thinking.

·

Native American texts try to increase

a community that understands “dialogical processes” by which Native cultures

often conceive of their own survival. That process shapes its readers’ aesthetic

and ethic responses (95)

·

Dialectics:

Oppositions with closed ends; dualities/binary oppositions

·

Dialogics:

open-ended, exchange

·

The dialectic ignores the dialogic by

reducing issues to binaries, while the dialogic continues to “dialogue” with the

dialectic by opening up more than binary possibilities.

·

Those who construct their world

through dialectical binaries, such as civilization v. wilderness, Euro-American

v. Indian, or Euro-American v. African American, miss the blurring of those

boundaries that drives the pragmatic unfolding of American identities and

differences.

·

Those who see the world through

dialogical interaction, through a nexus of exchange, continue to negotiate that

dialectical history in ways that seem invisible to dialecticians. These are the

perennially “vanishing Indians” who continue to survive after five hundred

years of colonization’s dialectical materialism.

·

A dialogic can deconstruct each

binary instead of synthesizing them; through a reader’s fuller attention to

context, the dialogic begins to enter the reading process: some Indian

literatures suggest complex cultural exchanges instead of binary oppositions or

binary absorption or resistance between self and other, between tribes, or

between Indian and white (97)

·

We exchange with each other, rather

than disappear (absorb) or resist each other (fight).

·

Decolonializing Criticism

·

How then can critics participate in

the textual context of dialogic cultural survival? Critics can affirmatively

articulate modes of cultural interaction in the texts the elude domination,

assimilation, or co-optation and that make visible possibilities of cultural

survival through such processes as nexus of exchange.

·

The critic must start with the

premise that oral forms reflect particular ways of knowing, that they are

epistemological realities. They exist both as artifact and as process.

·

We can take a critical approach to

the complex field of Native American studies that begins to reflect certain

Native American ways/values.

·

We

can foster cooperation among

many critics, writers, folklorists, anthropologists, and art historians, all of

who can publish sensitive description of specific artistic traditions, not in

the style of the once-popular “definitive” accounts of “dying” traditions, but

in a way that shows both the continuity and the open-endedness of tribal ways.

·

Ethics: one can “give back” in a

variety of ways---by teaching, by writing, by round dancing when the invitation

goes out at a powwow, by just attending cultural events such as powwows, by

bringing food to a wake, or by coming over merely to hang out and visit.

Carter Revard (Osage), "Myth, History, and Identity Among the Osages and Other

Peoples"

American Indian autobiographies the notion of identity, how the individual

is related to world, people, self, differs from what we see in Euroamerican

autobiographies differ.

Euro-americans: story of birth to death

Geronimo (Apache): cosmic through geologic to tribal, subtribal, family and then

individual self that was Geronimo

Americans have untied their names and individual histories from place and nation

to an astonishing extent

Geronimo knew who he was and where he came from. In this story, the notions of

cosmos, country, self, and home are inseparable.

For Santee Sioux Charles Eastman, becoming Santee meant "learning the Santee

system of names for animals and plants, and how this system tied his sense of

personal identity to his sense of tribal identity and relationship to the

world of other-than-human "natural beings.

"The 'wild' Indian was tied to land, people, origins and way of life, by every

kind of human order we can imagine. 'History' and 'myth' and 'Identity' are not

three separate matters, here but three aspects of one human being" (136).

Greg Sarris, "The Woman Who Loved a Snake: Orality in Mabel McKay's Stories"

Context of story

important, especially in cross-cultural situations 144

Dialogics: open ended exchange

Listener as part of story; there is so much more than just the story and what

was said that is the story 143

story always changing

Literate tries to pin down, close

Orality opens

"Mabel's talk impedes these literate tendencies for closure by continually

opening the world in which oral exchange takes place" 143, 151

In Mabel's story the "real" and the "supernatural" are a "coexistent

reality."

Jenny wants to know what the snake "symbolizes." Mabel doesn't really understand

this question due to cultural differences/epistemologies. 142

Sarris says, "Mabel is saying: Remember that when you hear and tell my

stories there is more to me and you that is the story. You don't know everything

about me and I don't know everything about you. Our knowing is limited. Let our

words show us as much as we can learn together about one another. Let us

tell stories that help us in this. Let us keep leaning." 150

|