|

Tuesday 8/21

Welcome! This course

takes an American Indian Studies approach: we'll learn what Native people think

about themselves, about others, and the world, expressed through oral and

written literatures. We'll learn from Native

speakers and writers, and approach the material from a Native American perspective,

based on indigenous values and epistemologies.

3 Crucial Ideas to Understanding American

Indian people and their literatures:

1) American Indian tribes are sovereign and each defines its sovereignty

differently, given its own history and culture and treaty/executive order

acknowledgement. Tribes are sovereign primarily because they are asserting their

own will, not because the US granted it.

2) Each tribe has a continuing, unique

and rich cultural tradition, still alive and well today. Many urban Indians retain

ties to their homelands and live "Indian lives" in cities.

3) Nevertheless, Indians have

experienced overwhelming assimilation and genocidal forces due to US

policies and missionaries.

The theme of this course is Resistance and

Renewal, designating Native Americans' determination to resist complete

destruction by or assimilation into Settler culture. This is accomplished by a

continual renewal of culture and identity. Primary values of Native people

include, Respect * Reciprocity * Relationality

Additional Indigenous values/themes our course

will explore are:

Wisdom Sits in Place

All My Relations

Circle of Life

The Trickster/Resilience

Guest: Joe Roberts, UI Service Learning Program

Service Learning Opportunities: Tutoring at Plummer, Lapwai,

Native American Prisoners Inside-Out

Prison Exchange Project, Sapatq'ayn Cinema

Unit 1: Native Worldviews, Oral

Literatures

Thursday 8/23

Read: "Essential Understandings" button at

top left

and

PDF: Federal US American Indian Policy and

American Indian Demographics

Assignment 1: Write About today's discussion

Tuesday 8/28

Assignment 1 due

Video (30 min):

Native Voices: Resistance and Renewal in American Indian

Literature (includes authors Simon Ortiz, Joy Harjo, Paula

Gunn Allen, Leslie Marmon Silko, Greg Sarris, and Lucy Tapahanso. from the

online American literature survey american passages.

Assignment 2: Write a

2 page (typed, double-spaced) response to Native Voices.

Resources for the Video

Thursday

8/30

Share responses to Native Voices

"Huckleberries,"

Rodney Free, pp 1 - 56

to be a guest

to go inside the Tin Shed

to see from the inside out

to feel it

Storytellers Online:

Stories of the Lewis and Clark

Trail Tribes

Nimiipuu (Nez Perce)

About Stories

Santa Fe

Indian School Spoken Word Team

Tuesday 9/4

Animal Tales

excerpt from Salmon and His People: Fish and

Fishing in Nez Perce Culture, Landeen and Pinkham

excerpt from Nez Perce Coyote Tales: The Myth Cycle,

Walker and Matthews

Reading Graphic Literature:

Graphic Novels, Paul Gravett (pdf)

Group One: Trickster Tales

Dara, Conor, Latona,

Billy, Mason S, Meagan, Kirk

Trickster: Native American Tales: a

graphic collection

Thursday

9/6

About American Indian comics

Groups present from Trickster

Tuesday 9/11

Groups present from Trickster

Thursday

9/13

Conclude Trickster

Tuesday 9/18

Nez Perce Stories and Place

Visit from Nez Perce storyteller NAKIA WILLIAMSON

Thursday 9/20

About Horace Axtell

A Little Bit of Wisdom, Preface - 67

and read the Glossary on pp 215-217

Visit from Horace Axtell and Margo Aragon

Tuesday 9/25

Conclude, A little bit of

wisdom

Assign Exam 1 on Oral Literature and

Place: create groups to create stories

Coyote Story Project: form groups of 3 to create your own Coyote Story on

UI campus to illustrate the Indigenous concept "Wisdom Sits In Places"

Coyote, as you know, is a trickster, a transformer and a bungling egomaniac. But

he also tries to solve problems and make life better. He always

interacts with other animal people, sometimes competing with them,

sometimes cooperating with them--even helping them, though he often needs their

help as well. He's a genius and a fool. Both community-minded AND exceedingly

self-centered. Think about Coyote's attributes and those of the other animal

people. Through Coyote stories we learn how "things came to be," such as why

Grizzly Bear has a flat nose, and why death is permanent. Through these stories

we learn how to survive successfully in our communities and in the places we

live.

Your assignment is to form groups of 3 or 4, walk the UI Campus until you find

a "place" that you believe can tell a story. How did this "place"

come to be? And what lesson does it teach us? Create a story about your "place" that illustrates the

concept "Wisdom Sits in Places." The campus is a "culture" with practices,

rituals and they all originate in place (campus) and culture (university

practices). The learning goal is for you to "see from the inside out," rethink

place and to experience story creation and performance. Turn what seems like

"just" a place into a story. What evidence do you

find of Coyote and the animal peoples' adventures here?

brief thoughts about final projects

Service Learning updates

Groups for reports

Theories and approaches to Native

literature 2 groups

Perma Red and Indigenous Feminism 1 group

Winter in the Blood 2 groups:

the novel and the film

The Lesser Blessed 2 groups:

Dogrib origin story/Van Camp/the film

Humor in Native America

E N T E R T H E E X H I B I T B

E L O W:

Indian Humor Exhibit

at Smithsonian

Deloria (Lakota), "Indian Humor"

from Nothing But the Truth: An Anthology of Native American Literature (PDF)

Click on the "Indian Humor" button above left side of the screen and read . . .

For discussion:

What are the traditional as well as post-colonial functions of humor in Native societies?

What are

the advantages of employing humor in difficult contexts, such as the German

Holocaust? How does this apply to the American Holocaust?

Video clips from:

Charlie Hill on Richard

Pryor Show 1977

Dr. Greene's Original Pain

Reliever

The 1491's

Thursday 9/27

No Class: work on your exam/story

Tuesday 10/2

tell your Coyote stories & turn in written component

Thursday 10/4

Historical Trauma and Healing in Native America

Native American Studies as a field was created to support

American Indian self-determination and cultural revitalization. Thus, learning

about NA historical trauma and healing is important to the study and

understanding of Native American literatures. We will attempt to connect the pre-colonized life world of

Native Americans to colonized life worlds: how do both seek balance and

healing and balance through literary arts, oral and written.

Native Americans and the Trauma

of History, Duran, Duran, and Brave Heart (PDF)

Documentaries:

A Century of Genocide:

The Residential School Experience

Optional: For further reading on Historical

Trauma/Intergenerational Grief you may read:

Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, "The American

Indian Holocaust: Healing Unresolved Grief" (starts on p.60)(pdf)

Lisa Poupart, "The Familiar Face of Genocide: Internalized Oppression

Among Native Americans" (pdf)

Tuesday 10/9

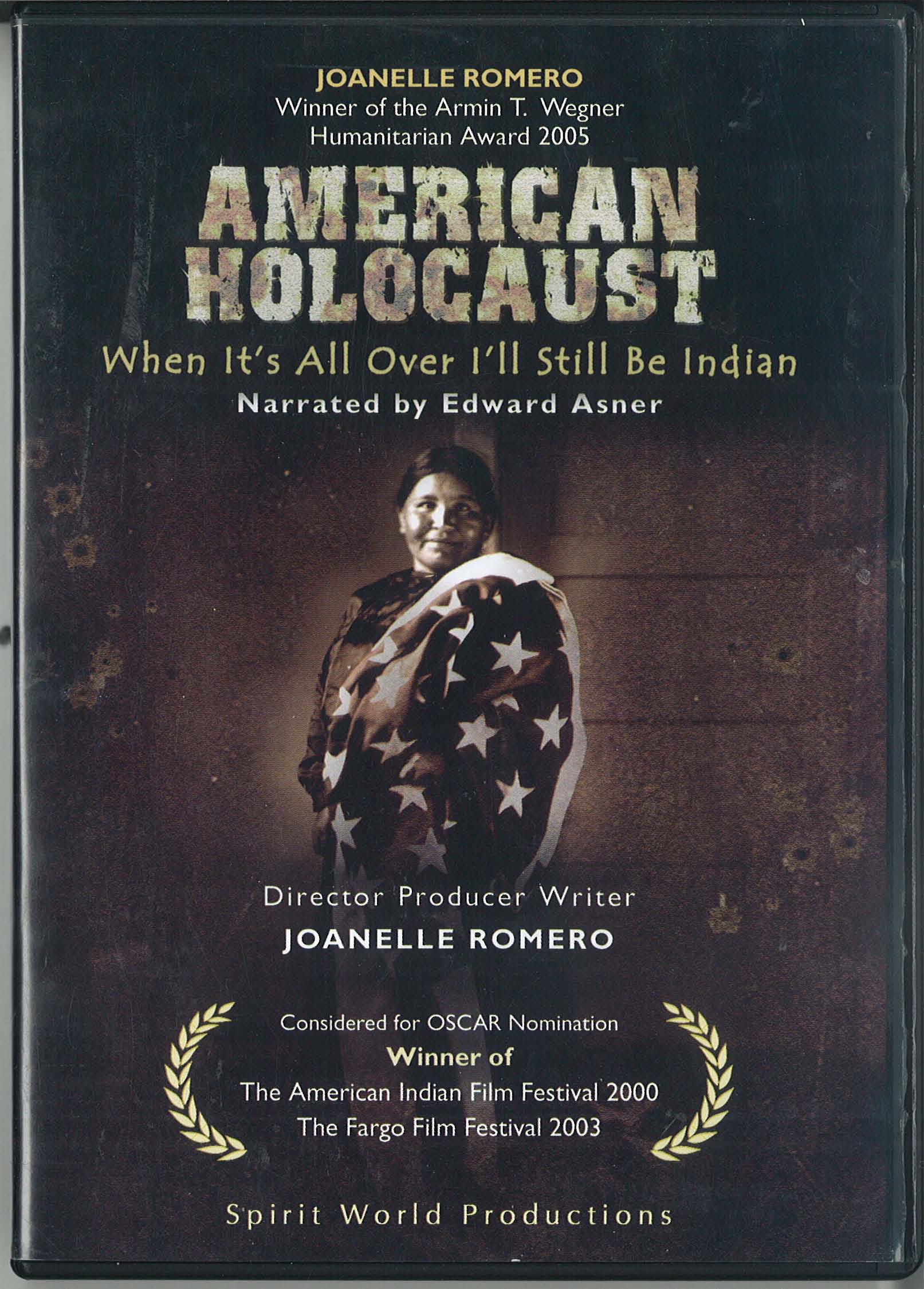

American Holocaust: When It's All Over I'll Still Be Indian

Free write: your response to the

Historical Trauma films

Discussion Questions for Duran:

What are colonialism and imperialism?

What are the effects of colonialism on the Native American "life world"?

How have Native Americans reacted to the system of colonization?

Understanding this history and the intergenerational trauma it produced is a

vital part of the healing and regenerative process for Native American people

today.

What is "Postcolonial thinking"?

What are "academic colonial

processes" ?

What is "epistemic violence"?

What is "counter-hegemonic ideology"?

Hegemony: Ideological/cultural domination by the assertion of

universality and neutrality and by disavowal of all other cultures forms or

interpretations. (68) A Eurocentric mode of representation of Native Americans

is a biased assessment of non-Western cultures.

What is the "Soul Wound"?

Why would loss of the traditional environment be a severe spiritual and

psychological injury?

What happens when your own government is the oppressor?

What are the ramifications for Native people when the "American holocaust" is

not acknowledged by the majority culture?

See top of p. 69 for a discussion of the inadequacy of western healing models,

and the idea that they actually can inflict "epistemic violence"

See bottom of p. 70 for a definition of "Postcolonial thought"

How can simply educating Native Americans (and other Americans) about historical trauma be healing?

Thursday 10/11

The Boarding School Experience

About Indian Boarding Schools

A Photo Gallery of the Indian Boarding School

Louise Erdrich (Ojibway),

"indian Boarding School: The Runaways"

Canadian Apology and

Acceptance by Tribal

Leaders and

Australian Apology

VIdeo:

Our Spirits

Don't Speak English

Andrew

Windyboy's testimony

For further reading: "American

Indian Boarding School Experiences: Recent Native Perspectives"

Tuesday 10/16

Silko, Leslie Marmon: "Lullaby" (pdf)

Handouts: Oppression Continuum and What is an Ally? (pdfs)

--what for you is most

significant about Native American historical trauma and intergenerational grief?

--what does being an ally mean to you?

--where are you on the continuum of racism? where do you want to be?

--how can non-Natives best be allies to Native people?

--how would becoming an ally help you, other people and the larger group?

Indigenous theories of & approaches

to literature

Thursday 10/18

Group One:

Simon Ortiz, Towards a National Indian Literature: Cultural Authenticity in

Nationalism"

Kim Roppolo,

"Toward a Tribal-Centered Reading of Native American Literature"

(pdf)

"Homing In," Wm. Bevis

"Communitism," Jace Weaver: That the People Might Live

David

Group Two:

"Mythic Realism," Louis Owens in Other Destinies

"Tribalography," Leanne Howe

"Survivance," Gerald Vizenor

"That's Raven's Talk: Holophrastic Approaches"

Kendra

Group Three:

Reports on Indigenous Feminism (2)

Dara and ?

Tuesday 10/23

Reports on

Author Debra Magpie Earling,

the

Flathead Reservation and history, setting for Perma Red

Kassidy, Katie, Laura,

Bridger, Spencer, Whitney

Map of Montana's

Tribal Nations

Brief Salish Tribal Timeline

1700s: The Salish acquired horses,

making them a target of raiding parties of Blackfeet and other enemies.

1804-6: The tribe

assisted the Lewis and Clark Expedition with food and horses. The expedition was

a catalyst for the fur trade which brought goods to make life easier, as well as

diseases, alcohol and guns.

1840-1841: In the early 1840's one

of their leaders had a "vision" of the "Blackrobes" who would come with

spiritual teaching. A group of Salish men traveled to St. Joseph's Mission on

the Potawatomi Reservation at Council Bluffs, Iowa to meet the "Blackrobes,"

requesting they come and bring spiritual teaching. Father Pierre-Jean DeSmet

left for the Bitterroot Valley, where he established the St. Mary's Mission

1855: Hellgate Treaty: the Salish ceded over 22 million acres to the

U.S.

1864: Catholics established a boys and girls boarding school on the

reservation

1872: The Salish were forced from their homeland in the Bitterroot

Valley to the Jocko Reservation (later the Flathead Reservation), a tragedy for

the tribe

1890: Ursuline nuns began a kindergarten which later grew into a grade

school and then a high school.

1891: forced removal of last few tribal members from the Bitterroot

Valley to the Flathead Reservation

1904: Flathead Allotment Act divided the land and opened it to white

settlement

1910: as result of the Dawes Act, homesteaders became the majority

landholders on the Flathead Reservation

1935: The Salish and Kootenai tribes of Montana joined to become The

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes

Debra Magpie

Earling

Debra Magpie Earling's debut novel Perma Red is something of a

miracle. The University of Montana creative writing professor began writing it

in 1984 and, over the years, it has been through at least nine different

rewrites, trimmed from an epic-length 800 pages to a compact 288, burned to a

crisp in a house fire, and rejected by publishers who loved the writing but

thought the original ending too dark and brutal. Through it all, Earling

persevered and the novel stands as a testament to her faith and patience.

Resources for Earling and Perma

Red:

"Facing Down Violence," Jan Johnson (pdf)

Read Perma Red, through Chapter

7(Officer Kicking Woman: here)

fyi: Debra's relative,

Chief Charlot

Map of

Perma Red Country

Thursday 10/25

Perma Red, through pp 218

(Charlie Kicking Woman: reservation death)

Tuesday 10/30 (Stick

Game in Commons Clearwater Rm at 11am)

Conclude Perma Red, (Louise: the long hunger - end

Group Four: Intro to James Welch and Winter in the Blood:

the novel and the movie ("Trailer")

Kiley, Keila, Briana, Eddy

Background on James Welch (Blackfeet/Gros Ventre)

James Welch at Internet

Public Library

Ploughshares (a literary journal) story on James Welch

The MOVIE

Winter in the Blood, Chaps 1 -14,

pp. Intro - 35

Thursday 11/1

Winter in the Blood, through Chapter 24; pp - 83

Tuesday 11/6

Read:

"The Social World of James Welch" by Matt Herman

conclude WITB

Assign Exam 2

Thursday 11/8

Visit from Steven Paul Judd (Distinguished American Indian Speakers

Series)

Tuesday 11/13

The Lesser Blessed

Group 5: The Lesser Blessed, Richard Van Camp

Derek, Saleeha, Justin, Claire, Kirsten, Edward

Dogrib Origin Story: "The Woman and the Pups"

INTRODUCING Richard Van

Camp

read his bio here on Nativewiki, hear

him read poetry, learn what he's up to--

The Lesser Blessed will soon be released as a movie! See the

Trailer

Sam McKegncy,

'Beautiful

Hunters with Strong Medicine': Indigenous Masculinity and Kinship in Richard Van

Camp's The Lesser Blessed"

Thursday 11/15

Final Paper/Project Proposal Due: Follow instructions at bottom of

"Final Project"

Exam 2 due

Deconstructing the Myths of the First "Thanksgiving"

Thanksgiving Break - 11/19 - 11/23

Native American Heritage Day 11/23

Tuesday 11/27

Professor returns Final

Project Proposals

Finish Discussion of The Lesser Blessed

Thursday 11/29

UNIT 2: POETRY

POETRY: Group 7: Melissa, Sarai, Amanda,

Becky, Sam

Brian Swann,

"Introduction: Only the Beginning," from Nothing But the Truth: An

Anthology of Native American Literature Ed. James Ruppert and John Purdy,

2001

Kimberly Blaeser (Anishinaabe), Nothing But the Truth:

"The Possibilities of a Native Poetics"

Contemporary Native American poetics are "infused with echoes of the song poems

and ceremonial literatures of the tribes, born out of the indigenous revolution,

filled with the dialogues of inter-textuality, sometimes linked to the cadence

and construction of 'an-other' language, frequently self-conscious, and often

resistant to genre distinctions and formal structures" (412).

Recognizable facets of Indian-authored

poetry:

1) a significant spiritual and physical landscape

2) an investment in political struggle (they carry history)

3) a search for or an attempt to articulate connections with the

individual, tribal or pan-Indian legacy

4) connections to the oral tradition

5) engages in framing a response to the perceived expectations of Native

literature, and/or how non-Natives have represented Indians.

"One function of American Indian poetry has

been to 'resist cultural erasure' to question the dominant narrative, and to

remember our histories clearly as a way to resist both amnesia and nostalgia."

"Literacy in English has not prevented

Indian writers from exploring the possibilities for articulating the truth of

their own visions through poetry. These visions come out of an exploration of

what it means to be Indian and what it means to come from a cultural and

historical past that is unique within American experience."

Poetry often serves to tell us about the

places we've been as a people or about the places we wish to be. What we admire

about it, or about the poets who make it, are the ways poetry may

succinctly distill and render human experience into language. Language is

a vehicle of ceremony [and healing]. " poet Janice Gould (Maidu)

The Oral World into Written Poetry

from

Navajo Nightway Chant

to

The

Delight Song of Tsoai-Talee --N. Scott Momaday

|

I am a feather on the

bright sky

I am the blue horse that runs in the plain

I am the fish that rolls, shining, in the water

I am the shadow that follows a child

I am the evening light, the lustre of meadows

I am an eagle playing with the wind

I am a cluster of bright beads

I am the farthest star

I am the cold of the dawn

I am the roaring of the rain

I am the glitter on the crust of the snow

I am the long track of the moon in a lake

I am a flame of four colors

I am a deer standing away in the dusk

I am a field of sumac and pomme blanche

I am an angle of geese in the winter sky

I am the hunger of a young wolf

I am the whole dream of these things

You see, I am alive, I am alive

I stand in good relation to the earth

I stand in good relation to the gods

I stand in good relation to everything that is beautiful

I stand in good relation to the daughter of Tsen-tainte

You see, I am alive, I am alive

|

from Angle of Geese, 1974

from Angle of Geese, 1974 |

Native Poetry Records and Retells History

The Ghost Dance

Ghost

Dance Songs

Massacre at Wounded Knee

N. Scott Momaday, "December 29, 1890: Wounded Knee Creek"

December 29, 1890 --N. Scott

Momaday

|

|

Wounded Knee Creek

In the shine of photographs

are the slain, frozen and black

on a simple field of snow.

They image ceremony:

women and children dancing,

old men prancing, making fun.

In autumn there were songs, long

since muted in the blizzard.

In summer the wild buckwheat

shone like fox fur and quillwork,

and dusk guttered on the creek.

Now in serene attitudes

of dance, the dead in glossy

death are drawn in ancient light.

|

from In the Presence of the Sun, 1992

from In the Presence of the Sun, 1992 |

(Many Excellent Native

American Poems for your perusal)

Tuesday 12/4

WENDY ROSE

Wendy

Rose (background/bio)

"I Expected My Skin and My Blood to Ripen"

Does poetry influence policymaking?

Native American Graves Repatriation Act

(1990)

Nez Perce Repatriation Notice

Sherman Alexie

video on his newest book of poetry, "Faces."

Sherman Alexie, "My Heroes Have Never Been Cowboys"

1.

In the reservation textbooks, we learned Indians were invented in 1492 by a

crazy mixed-blood named Columbus. Immediately after class dismissal, the Indian

children traded in those American stories and songs for a pair of tribal shoes.

These boots are made for walking, babe, and

that’s just what they’ll do. One of these days these boots are gonna walk all

over you.

2.

Did you know that in 1492 every Indian instantly became an extra in the Great

American Western? But wait, I never wondered what happened to Randolph Scott or

Tom Mix. The Lone Ranger was never in my vocabulary. On the reservation, when we

played Indians and cowboys, all of us little Skins fought on the same side

against the cowboys in our minds. We never lost.

3.

Indians never lost their West, so how come I walk into the supermarket and find

a dozen cowboy books telling How The West Was

Won? Curious, I travel to the world’s largest shopping mall, find the

Lost and Found department. “Excuse me,” I say. “I seem to have lost the West.

Has anyone turned it in?” The clerk tells me I can find it in the Sears Home

Entertainment Department, blasting away on fifty televisions.

4.

On Saturday morning television, the cowboy has fifty bullets in his six-shooter;

he never needs to reload. It’s just one more miracle for this country’s heroes.

5.

My heroes have never been cowboys; my heroes carry guns in their minds.

6.

Win their hearts and minds and we win the war.

Can you hear that song echo across history? If you give the Indian a cup of

coffee with six cubes of sugar, he’ll be your servant. If you give the Indian a

cigarette and a book of matches, he’ll be your friend. If you give the Indian a

can of commodities, he’ll be your lover. He’ll hold you tight in his arms,

cowboy and two-step you outside.

7.

Outside, it’s cold and a confused snow falls in May. I’m watching some western

on TBS, colorized, but the story remains the same. Three cowboys string

telegraph wire across the plains until they are confronted by the entire Sioux

nation. The cowboys, 19th century geniuses, talk the Indians into touching the

wire, holding it in their hands and mouths. After a dozen or so have hold of the

wire, the cowboys crank the portable generator and electrocute some of the

Indians with a European flame and chase the rest of them away, bareback and

burned. All these years later, the message tapped across my skin remains the

same.

8.

It’s the same old story whispered on the television in every HUD house on the

reservation. It’s 500 years of that same screaming song, translated from the

American.

9.

Lester Falls Apart found the American dream in a game of Russian Roulette: one

bullet and five empty chambers. “It’s Manifest Destiny,” Lester said just before

he pulled the trigger five times quick. “I missed,” Lester said just before he

reloaded the pistol: one empty chamber and five bullets. “Maybe we should call

this Reservation Roulett,” Lester said just before he pulled the trigger once at

his temple and five more times as he pointed the pistol toward the sky.

10.

Looking up into the night sky, I asked my brother what he thought God looked

like and he said “God probably looks like John Wayne.”

11.

We’ve all killed John Wayne more than once. When we burned the ant pile in our

backyard, my brother and I imagined those ants were some cavalry or another.

When Brian, that insane Indian boy from across the street, suffocated

neighborhood dogs and stuffed their bodies into the reservation high school

basement, he must have imagined those dogs were cowboys, come back to break

another treaty.

12.

Every frame of the black and white western is a treaty; every scene in this

elaborate serial is a promise. But what about the reservation home movies? What

about the reservation heroes? I remember this: Down near Bull’s Pasture, Eugene

stood on the pavement with a gallon of tequila under his arm. I watched in the

rearview mirror as he raised his arm to wave goodbye and dropped the bottle,

glass and dreams of the weekend shattered. After all these years, that moment is

still the saddest of my whole life.

13.

Your whole life can be changed by the smallest pain.

14.

Pain is never added to pain. It multiplies.

Arthur, here we are again, you and I, fancydancing through the geometric

progression of our dreams. Twenty years ago, we never believed we’d lose. Twenty

years ago, television was our way of finding heroes and spirit animals. Twenty

years ago, we never knew we’d spend the rest of our lives in the reservation of

our minds, never knew we’d stand outside the gates of the Spokane Indian

Reservation without a key to let ourselves back inside. From a distance, that

familiar song. Is it country and western? Is it the sound of hearts breaking?

Every song remains the same here in America, this country of the Big Sky and

Manifest Destiny, this country of John Wayne and broken treaties. Arthur, I have

no words which can save our lives, no words approaching forgiveness, no words

flashed across the screen at the reservation drive-in, no words promising either

of us top billing. Extras, Arthur, we’re all extras.

Horses, by Sherman Alexie

for your perusal:

A Serious Collection of Alexie Poems

Joy Harjo (Creek)

"Stories and songs are like humans who when

they laugh are indestructible" Joy Harjo

Joy Harjo, Text of

"A Postcolonial

Tale"

"I Give You Back"

|

I

Give You Back --Joy Harjo

|

|

I release you, my beautiful and terrible fear. I

release you. You were my beloved and hated twin, but now, I don't know

you as myself. I release you with all the pain I would know at the

death of my daughters.

You are not my blood anymore.

I give you back to the white soldiers who burned down

my home, beheaded my children, raped and sodomized my brothers and

sisters. I give you back to those who stole the food from our plates

when we were starving.

I release you, fear, because you hold these scenes in

front of me and I was born with eyes that can never close.

I release you, fear, so you can no longer keep me naked

and frozen in the winter, or smothered under blankets in the summer.

I release you I release you I release you I release

you

I am not afraid to be angry. I am not afraid to

rejoice. I am not afraid to be black. I am not afraid to be white. I

am not afraid to be hungry. I am not afraid to be full. I am not

afraid to be hated. I am not afraid to be loved.

to be loved, to be loved, fear.

Oh, you have choked me, but I gave you the leash. You

have gutted me but I gave you the knife. You have devoured me, but I

laid myself across the fire. You held my mother down and raped her,

but I gave you the heated thing.

I take myself back, fear. You are not my shadow any

longer. I won't hold you in my hands. You can't live in my eyes, my

ears, my voice my belly, or in my heart my heart my heart my heart

But come here, fear I am alive and you are so afraid

of dying.

from She Had Some

Horses, 1983 |

|

Linda Hogan

Who

Will Speak? --Linda Hogan

|

|

If all the animals came from the hills,

if all the fish

came from the rivers,

and the birds came down from the sky

we would

know our lives,

small,

somewhere between the mountain

and the ant.

We would see what we do pass by

and return

around earth's curve.

All I know are these rivers,

the air and wind

carving

down the trees

with their invisible hands

until the trees are bent

figures of old men

and then only the empty space,

a longing that

passes.

And that sorrow says,

the animals,

who will speak for

them?

Who will make houses of air

with their words?

And the mouth of a man,

the tongue

that belongs to

grass and light

and the four-legged creatures.

He speaks of tomorrow.

He gives voice to the small animals.

He gives a seat to the eagles.

Words for the fish.

The golden light of creation.

Light. Lumine. The world returns.

I do not want to break this spell.

I do not want the

words to fall away.

I do not want to break this spell.

(for Oren Lyons, 1978)

|

|

from Eclipse,

1983 |

Louise Erdrich (Anishinaabe)

"Dear John Wayne"

August and the drive-in picture is packed.

We lounge on the hood of the Pontiac

surrounded by the slow-burning spirals they sell

at the window, to vanquish the hordes of mosquitoes.

Nothing works. They break through the smoke screen for blood.

Always the lookout spots the Indian first,

spread north to south, barring progress.

The Sioux or some other Plains bunch

in spectacular columns, ICBM missiles,

feathers bristling in the meaningful sunset.

The drum breaks. There will be no parlance.

Only the arrows whining, a death-cloud of nerves

swarming down on the settlers

who die beautifully, tumbling like dust weeds

into the history that brought us all here

together: this wide screen beneath the sign of the bear.

The sky fills, acres of blue squint and eye

that the crowd cheers. His face moves over us,

a thick cloud of vengeance, pitted

like the land that was once flesh. Each rut,

each scar makes a promise: It is

not over, this fight, not as long as you resist.

Everything we see belongs to us.

A few laughing Indians fall over the hood

slipping in the hot spilled butter.

The eye sees a lot, John, but the heart is so blind.

Death makes us owners of nothing.

He smiles, a horizon of teeth

the credits reel over, and then the white fields

again blowing in the true-to-life dark.

The dark films over everything.

We get into the car

scratching our mosquito bites, speechless and small

as people are when the movie is done.

We are back in our skins.

How can we help but keep hearing his voice,

the flip side of the sound track, still playing:

Come on, boys, we got them

where we want them, drunk, running.

They'll give us what we want, what we need.

Even his disease was the idea of taking everything.

Those cells, burning, doubling, splitting out of their skins.

discuss the setting, speaker, imagery and themes

"The Strange People," Louise Erdrich

The antelope are strange people ... they are beautiful to

look at, and yet they are tricky. We do not trust them. They appear and

disappear; they are like shadows on the plains. Because of their great

beauty, young men sometimes follow the antelope and are lost forever. Even

if those foolish ones find themselves and return, they are never again right

in their heads.

—Pretty Shield,

Medicine Woman of the Crows

(transcribed and edited by Frank Linderman (1932)

All night I am the doe, breathing

his name in a frozen field,

the small mist of the word

drifting always before me.

And again he has heard it

and I have gone burning

to meet him, the jacklight

fills my eyes with blue fire;

the heart in my chest

explodes like a hot stone.

Then slung like a sack

in the back of his pickup,

I wipe the death scum

from my mouth, sit up laughing

and shriek in my speeding grave.

Safely shut in the garage,

when he sharpens his knife

and thinks to have me, like that,

I come toward him,

a lean gray witch

through the bullets that enter and dissolve.

I sit in his house

drinking coffee till dawn

and leave as frost reddens on hubcaps,

crawling back into my shadowy body.

All day, asleep in clean grasses,

I dream of the one who could really wound me.

Not with weapons, not with a kiss, not with a look.

Not even with his goodness.

If a man was never to lie to me. Never lie to me.

I swear I would never leave him.

Louise Erdrich, "The Strange People" from Original Fire:

Selected and New Poems. Copyright © 2003 by Louise Erdrich. Reprinted with

the permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

Thursday, 12/6

Phil George (Nez Perce)

from his book Kautsa (Grandmother)

Name Giveaway

That teacher gave me a new name. . . again.

She never even had feasts or a giveaway!

Still I do not know what “George” means:

and now she calls me “Phillip.”

Two Flocks of Geese

Lighting Upon Still Waters

must be a

name too hard to remember.

Salmon Return

Like many Grandfathers before me,

I spear Salmon: splashing, flapping.

These echoing waters no longer your home.

Up Celilo Falls you will dance no more.

Cleansed, Grandmother will weave

willows into your needle-boned flesh.

Beside night fires you will roast—

Fat oozing, dripping, sizzling.

My people will not go hungry.

We fast. We sing. We feast.

May your spirit always live, my friend,

if even in the Moon of High Waters.

From saltwaters you swim upstream to die.

We remember: “Return home to die.”

Moon of Huckleberries

Black Bear sang, drumming on a log:

“Come, bring your biggest baskets

To the best berry patches.

I’ll show you.”

“If you maidens get lost—

Just follow my dung,

Just follow my dung.”

Black Bear sang, drumming on a log.

Tiffany Midge

(Standing Rock Sioux), MFA (UI)

About Tiffany Midge

A

selection of Tiffany's poems

be sure to read all the poems here

and one of Tiffany's favorites:

Nora Dauenhauer "How to Cook a Wild Salmon"

http://poeticsandpolitics.arizona.edu/dauenhauer/salmon.htm

Final Paper Due Monday 12/10, BRINK 200, my mailbox by

5:00 PM

Have a Great Break!

______________________________________________________________________________________

from previous semesters . . .

New Engl 484 presentation.ppt

HooPalousa basketball game,

7:30 Memorial Gym with Sherman Alexie

Sherman Alexie's website

Video Clips: Sherman Alexie: Open All Night (NOW/PBS)

Video Clip: 2001 World Heavyweight Poetry Championship with Sherman Alexie

Alexie on Colbert

Lecture:

Sherman Alexie's Postmodern Aesthetics

FABULOUS INTERVIEW with Alexie on trauma,

writing

discuss Flight

Optional secondary readings:

S. Evans, "Sherman

Alexie's Open Containers"

PBS/POV "Border Talk" with Sherman Alexie

also check out: RED ROAD TO SOBRIETY

Ortiz (Acoma Pueblo), "Towards a National Indian Literature: Cultural

Authenticity in Nationalism" 120-125

1. Explain the ceremonies of Acquemeh and how they are "authentically"

Indian.

2. How have Native people responded to colonialism, according to Ortiz?

3. What quality or qualities, for Ortiz, most characterizes NA literature and

people/communities?

* Colonialism: what is it? where is it?

how does it work?

Tuesday 9/07

Simon Ortiz, "The Killing of a State

Cop" 321

Leslie Marmon

Silko, "Tony's Story," 362

Cook-Lynn, "The Power of Horses," 226

Discussion questions:

1. Why do you think both Silko and Ortiz chose to apply their imagination to an

historical event?

2. What are the major differences between the stories and what effect(s)

do these differences have?

3. Choose a passage from each story that represents for you one of the author's

major concerns/themes.

4. Which story--Silko or Ortiz's--did you most enjoy and why?

5. What role does the Tribe's oral stories play in this story? How does

the story employ Momaday's "myth, history and memoir/personal" ? How do

both the ancient story of the horse and the mother's story affect the father and

daughters' actions? What IS the power of horses?

of the profane.

(NBT) Pauline Johnson, "As It Was in the Beginning,"

(1917) p. 282

1. choose the passage you find most powerful in the story

2. explore the animal imagery and how it is used

3. consider the first line of the story and the final two lines, "They account

for it by the fact that I am a Redskin.

They seem to have forgotten I am a woman" (288).

4. what are the major themes of the story, and perhaps Johnson's

"message"?

5. does the story resonate in any ways with the boarding school essay

above?

For further reading: Silko, Leslie Marmon, "Lullaby"

Prof. Johnson's Nez Perce Jazz Band Research (if time)

The Power of Place/Place-Based Religion in Native America

Video clip: In the Light of Reverence (www.sacredland.org)

(excerpt) NOW ON RESERVE

for further reading:

www.sacred-sites.org

www.ienearth.org (Indigenous Environmental

Network)

Intro to James Welch (Blackfoot/Gros

Ventre) and 19th Century Northern Plain culture/history

Welch's novel, Winter in the Blood, is currently being made into a movie

with filming occurring in Montana

FOOLS CROW HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL BACKGROUND

FOOLS CROW Parts 1, 2

and 3-- Look at the Map in the back of the book--learn Blackfeet country and

important places in the novel

For Discussion:

1. What are the setting, situation and point of view or the narrator?

Describe our two protagonists. What are some of the Blackfeet values

communicated in this early part of the novel?

2. What are some of the names for the animals Welch has named and why do you

think he chose to this language?

What effect do these names have on you?

3. What evidence is there within the novel that the buffalo economy of the

Pikuni is changing? What is their response to the change?

4. What are the expectations for young Blackfeet men in terms of being accepted

as adults in the community? What skills, values and behaviors demonstrate male

maturity? What defines success and status? How does White Man's Dog meet or not

meet these expectation? How does Fast Horse meet or not meet these expectations?

5. How do the Pikuni define and acquire material wealth? How does this influence

their behavior toward other tribes? Toward traders? Settlers? How do the settlers

define and acquire material wealth? How does this influence their behavior

toward the tribes? Toward the traders?

6. What role do different perceptions of land ownership play in the conflicting

economies of the Pikuni and the settlers?

7. Explain a "vow" and its value to the Blackfeet.

8. What are the expectations for young Blackfeet women in terms of being

accepted as adults in the community? What skills, values, and behaviors

demonstrate female maturity? What defines success and status?

9. Discuss gender roles and division of labor in Pikuni society?

10. What is the purpose of the Sun Dance ceremony? Is it analogous to traditions

in other cultures?

11. How do the Pikuni define warfare? What are their goals? What is

permissible and impermissible in their acts of war? Why did the Blackfeet war

against the Crow?

FOOLS CROW

Parts 4 and 5

12. What is the significance of the conversation between Raven and Fools

Crow? In terms of worldview, what does Welch suggest through the relationships

the Pikuni have with animals?

13. Why does Welch call whites "Napikwans" and how has the Pikuni's attitude

toward them changed from the beginning of the novel?

14. What statement is the novel making about justice? What does Kipp mean when

he thinks, "These people have not changed, but the world they live in has"

(252)?

15. In chapters 21 and 22, what are the different chiefs and their philosophical

position on the conflict with the Napikwans. What would you advise in the

council meeting?

16. Where does Fools Crow journey? What is the symbolism of the turnips?

Who is Feather woman and what does Fools Crow learn from her? How are they

similar?

What is

honor to Blackfeet?

Where is the hope in chapters 25-32?

|