|

|

Big Horn Medicine Wheel |

Big Horn Medicine Wheel

|

|

Big Horn Medicine Wheel |

Source: http://solar-center.stanford.edu/AO/bighorn.html

|

|

| Crow Sundance Lodge | The Wagon Wheel |

It was the summer of 1974 and I was conducting my first

ethnographic field work.

As mentioned earlier, I was a graduate student at

the time, invited by the Apsáalooke to assist with helping “inform and educate”

the professional-trained but inexperienced non-Indian doctors who served in the

Indian Health Service.

The IHS physicians were having a difficult time

communicating with their tribal patients, especially the elders and the more

traditional members.

Working with the elders, I helped put together an

extended essay on how tribal members understood and approached illness and

healing, all from their perspectives, an essay the doctors would use to better

understand and hopefully communicate with their patients.

And in the course of this project I was introduced to one of the most amazing ways of looking at and experiencing the world, indeed creating the world. This world view, this behavior was repeatedly reflected in an uncanny ability of individuals to simultaneously travel distinct ways of life, as for example, of being a sincere Sundancer, devout Christian, a competent Indian Health Service nurse, and doing so with such ease.

This ambidextrous ability was wonderfully exemplified in the lives of

Tom and

Susie Yellowtail. Tom was an

akbaalía, a traditional healer, and the Sundance Chief for his people; and he was a devout Baptist. Susie danced alongside her husband in the Big Lodge and practiced Western biomedicine, in fact, was the first American Indian registered nurse in this country. On various occasions Susie was appointed to Presidential Councils, and

traveled widely throughout the United States representing Indian peoples. While in the Sundance Lodge, Tom danced with the whistle and prayed to

Akbaatatdía, “the Maker of All

Things First”; while in the “Little Brown” Baptist Church he read from the Good

Book and prayed to Jesus Christ. While in the Sundance Lodge, Susie

applied Indian medicine; while in the Indian Health Service Hospital she

prescribed Western biomedicine. But the Bible and the stethoscope were

never brought into the Sundance, or the Eagle-bone whistle never into the

Church. And while the Eagle

feathers of an akbaalía

(literally, “one who doctors”) might be fanned over a patient in the hospital,

the prayers and songs of the akbaalía

are offered only in the privacy of the patient’s room,

distinct from the care provided by the physician and nurse.

Each way of prayer and of healing, each way of behaving has

its own path, distinct from the other, each with its own integrity.

Yet all paths could be traveled, freely jumping

between and on each of them, all leading to the same source.

This powerful notion was appropriately symbolized

when in October of 1993 in Chicago Tom, in Eagle-feather headdress and full

regalia, shared the podium with some of the world’s foremost religious leaders,

including the Dalai Lama, and offered words of prayer at the 100th anniversary

of the Council for a Parliament of the World’s Religions. Tom’s Apsáalooke

prayer for world peace was so easily heard, mingling and merging with the over

8,000 other spokespeople from the world’s different religions – Christian,

Muslim and Jew, Hindu, Buddhist and Taoist, and American Indian.

* * *

He

stands there, in Eagle-feather headdress and beaded buckskin regalia, with an

Eagle-feather fan in hand, sharing the podium with some of the world’s foremost

religious leaders, including the Dalai Lama.

First speaking in his Apsáalooke language and then

in English, he offers words of prayer for world peace and compassion for all.

He is an

akbaalía,

“one who doctors others,” a medicine man, a Sundance Chief, and his words are

readily received by the over 8,000 in attendance – Christian, Muslim and Jew,

Hindu, Buddhist and Taoist alike.

Like many others from his own community in Montana,

he demonstrates an uncanny ability to speak and travel multiple and distinct

paths simultaneously, for him the ways of both the Sundance and of Christianity.

While in the Sundance Lodge, he dances with

Eagle-plumes, blows the Eagle-bone whistle and prays to

Akbaatatdía,

“the Maker of All Things First.”

While in the “Little Brown” Baptist Church he reads

from the Good Book, partakes of the Lord’s Supper and prays to Jesus Christ.

He is able, with competence, to effectively

communicate and participate with others, indeed nurture and support others, from

diverse communities, so distinct and seemingly mutually exclusive.

* * *

Tom Yellowtail, who became one of my most prominent and enduring teachers, offered the following understanding of how to travel distinct ways of life. Using imagery he felt I could relate to, he spoke of the world as a great “Wagon Wheel.” Tom was intimately familiar with the Wheel, as reflected in the rock Medicine Wheel to the south of his Wyola home and as structured into the Sundance Lodge and the pattern of its dancers.

From its perch high atop the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming,

the rocks of the Medicine Wheel have endured since time immemorial, the

recipient of countless pilgrimages and prayers. Its 28 spokes of rock were

linked by an outer rim of rocks some eighty feet in diameter and a central rock

cairn of some two feet in height.

As Tom has told in his favorite oral tradition, it

was Burnt Face, a young boy, horribly disfigured, deeply scarred, who first

traveled so long ago to these mountains to fast and offer prayer, and who

assembled these rocks as a gift to the Awakkulé, “Little People” who inhabited

the area, seeking their help. It’s the image of the Wagon Wheel that was offered.

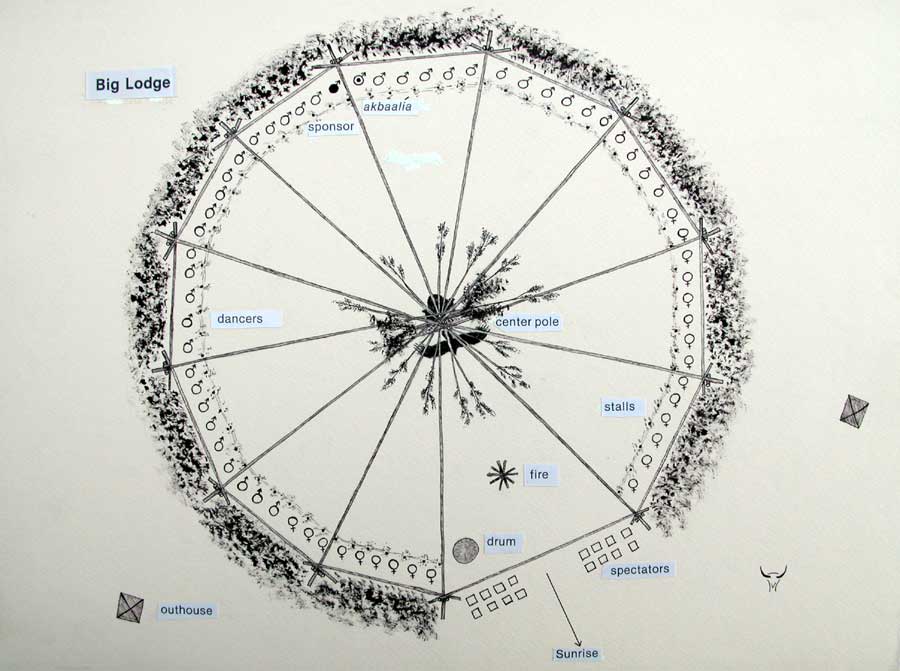

Imagine the Apsáalooke Sundance Lodge from the eye of a

soaring Eagle. The Big Lodge is anchored by its cottonwood forked-tree,

the Center Pole, from which twelve over-head poles radiate out to shorter posts

to form the rim of the Lodge some seventy to eighty feet in diameter, all

enclosed by cut trees and brush, its door open to the rising morning Sun.

For three and sometimes four days, the over one hundred participants would fast

from food and water, and offer prayer and dance for loved ones. To the

beat of the drum and song, and with Eagle-bone whistles in their mouths and

Eagle-plumes in hand, men and women charge the Center Pole, with its Buffalo

head and Eagle suspended from its fork, and then dance back to their stalls, and

then charge again, and again. Each dancer has made his or her own

individual vow to the Creator to give of him or herself for a loved one in need,

each

dancer

distinct in intentions and expression from the others. Nevertheless, all

the dancers are united as one as they blow their Eagle-bone whistles to the beat

of the drum, and as they stand before the Center Pole and offer burnt tobacco in

prayer, or as they might receive a blessing or healing, or even a visit from

perhaps the Buffalo, or Eagle, and be given a special gift, a “Medicine.”

The Apsáalooke name their Sundance Lodge is

Ashkísshe

– “imitation lodge” – in replication of the world, a microcosm of the greater

macrocosm, a reflection, a mirror.

Each of the unique spokes are dancing, among the

many collective diverse spokes, all in unison, united by the ubiquitous spirit

of whistle and drum, under the gaze of the Center Pole, of

Akbaatatdía,

the Creator, the

axis mundi,

anchoring and permeating the many spokes equally.

The image of the Wagon Wheel is seen and danced and

experienced, and brought forth.

And Tom went on to say, “The spokes of the wagon Wheel . .

are the various paths to the hub . . . the different religions . . the different

peoples of the world . . . each with their own ways . . their own languages . .

their own traditions . . . . . . but each spoke is

equally

important . . . that Wheel just wouldn’t turn if some spokes were longer than

others . . if some were taken out all together . . . . all the spokes are needed

if the Wheel is gonna to turn . . . . . . but all the spokes are linked to the

same hub . . . the same Creator . . . . each religion . . each spoke might call

the Creator by a different name . . . . but the prayers of all religions are

heard by the Creator . . . . . . . if the Wheel is to turn.”

Spokes unique, spokes collectively diverse; a hub

and rim unifying, ubiquitous, universal.

For Tom and Susie, and so many others, there need not be investment solely in a single spoke, need not choose sides, but choice to travel the many spokes. For Tom and Susie Yellowtail they could effectively dance the varied paths, the many spokes, when acknowledging the indispensable and interdependent relationship of the many dances within the inexorable, greater whole, the anchoring hub and encompassing rim, while at the same time distinguishing the unique integrity and the separate significance of each of the many dances, discerning on which path it is appropriate to dance this or that dance, each way of knowing and experiencing the world, each spoke. They can effectively dance when acknowledging the anchoring hub and distinguishing the many spokes. Without such, there would be little turning of the Wheel.

As we have noted, the Apsáalooke term for a clan is

appropriately, ashammaléaxia, “as driftwood lodges,” the social unit comprised

of several matrilineally-related, extended families. It's a term with

broad application. Imagine looking out onto the Bighorn River.

Individual pieces of driftwood don't do well in the fast moving currents, bashed

against a boulder there, and submerged in an eddy here. But there along

the river's bank the driftwood is lodged into a large bundle, each of the many

logs of driftwood in critical relationship with another, each supporting one

another, the whole enduring well in that turbulent river of life. And what

can bind the driftwood so tightly is a relationship expressed broadly by the

Apsáalooke practice of ammaakée, “give away” – of giving to and sharing with

others, with all those in need.

The Wheel-ashammaléaxia

metaphor

has facilitated the separate integrity of each of the many

while embedding them within an interdependency of the greater whole. The

Wheel-ashammaléaxia can thus provide a map for traveling the many paths without

dilemma, without having to make an either-or choice.

It’s a map that can chart a course, a map that can

create a path, when done with “competence.”

It’s a map of the world, brought to life in deed and

action, embedded by values of inclusion, of interconnection, of equality.

Regardless of how seemingly irrevocably distinct

from the other, the varied paths we encounter can be traveled without threat of

their mutual exclusivity.

But it is a matter of knowing your map, of knowing its

terrain.

For Tom and Susie there was a critical competency in

knowing which context and setting to be a devout Christian and a sincere

Sundancer, a skilled nurse, and a spiritual healer.

Knowing the map goes beyond just acknowledging or

even just respecting the distinctions of the spokes; its hard work, it takes

effort.

Tom and Susie repeatedly demonstrated their capacities to

effectively converse and communicate with Baptist parishioners, with Sundancer

participants, and with Indian Health Service practitioners alike, of applying

the subtle etiquette, nuances and languages of each.

While such distinct communities, Tom and Susie

worked with the members of each so easily, always in collaboration, helping

sustain their respective “Little Brown Church,” Sundance Lodges, and IHC

Hospital communities, without “mutual exclusivity.”

It

was little wonder that Tom, as Alan Old Horn, were at ease incorporating overtly

Euro-American images to convey essential and nuanced Indigenous meanings, that

of the “tin shed” and even a colonial-laden “wagon wheel.”

It’s a competency in knowing that only when the

individual logs of driftwood are kept distinct and strong in relation to the

others does the lodged driftwood survive.